Achieving SDG 3 is intricately intertwined with the realization of other SDGs that affect key determinants of health. For instance, SDG 1 (no poverty) and SDG 2 (zero hunger) can significantly impact health outcomes. SDG 4 (quality education) shapes behaviours and lifestyles with high impacts on health. SDG 5 (gender equality) is crucial for addressing gender-based health disparities, while SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation) underpins disease prevention. SDG 10 (reduced inequalities) supports equity in access to care through universal health coverage grounded in primary health care. SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) is essential for improving physical and social environments, and securing resources for health and well-being. SDG 13 (climate action) supports more climate-resilient and environmentally sustainable health systems, and helps ensure that health is at the centre of climate change mitigation policies. SDG 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions) empowers national institutions to put in place and monitor ambitious SDG responses. SDG 17 (partnerships for the goals) mobilizes partners to follow-up on and support the achievement of health-related SDGs.5

The majority of Arab countries have included the right to health in their constitutions.6 All have adopted legislation and/or national policies and plans on health. The region’s SDG 3 policy landscape has more commonalities than differences.

Most States are extending the coverage of health insurance schemes to reach more people. Common approaches have included reviewing income levels under subsidized civil health insurance schemes and expanding coverage to more population groups, such as migrants and refugees, older persons, the unemployed, the self-employed and informal sector workers.

Most States are extending the coverage of health insurance schemes to reach more people. Common approaches have included reviewing income levels under subsidized civil health insurance schemes and expanding coverage to more population groups, such as migrants and refugees, older persons, the unemployed, the self-employed and informal sector workers.

Countries of different income levels are strengthening primary health-care delivery systems at the community level, including in underserved rural areas and refugee camps, to reduce the burden on public hospitals, increase access to comprehensive health services and achieve universal health coverage. Key efforts15 include infrastructure development, particularly the construction and renovation of primary health-care facilities, and improved referral networks between primary health-care centres and hospitals.

Countries of different income levels are strengthening primary health-care delivery systems at the community level, including in underserved rural areas and refugee camps, to reduce the burden on public hospitals, increase access to comprehensive health services and achieve universal health coverage. Key efforts15 include infrastructure development, particularly the construction and renovation of primary health-care facilities, and improved referral networks between primary health-care centres and hospitals.

Most countries have policies on sexual and reproductive health, maternal health, and the health of infants, children and adolescents, but lack integrated services19 for improved outcomes. A global World Health Organization (WHO) policy survey shows that with few exceptions, Arab countries have covered between 75 and 99 per cent of 16 related policy areas.20 Typically covered areas include family planning and contraception; antenatal, childbirth and postnatal care; and child health. Less covered areas comprise cervical cancer prevention and control, early childhood development, adolescent health and violence against women (see chapter on SDG 5 for legislation on combatting violence against women).

Most countries have policies on sexual and reproductive health, maternal health, and the health of infants, children and adolescents, but lack integrated services19 for improved outcomes. A global World Health Organization (WHO) policy survey shows that with few exceptions, Arab countries have covered between 75 and 99 per cent of 16 related policy areas.20 Typically covered areas include family planning and contraception; antenatal, childbirth and postnatal care; and child health. Less covered areas comprise cervical cancer prevention and control, early childhood development, adolescent health and violence against women (see chapter on SDG 5 for legislation on combatting violence against women).

To address the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases, many Arab countries have developed multisectoral strategies or action plans for various diseases and common risk factors, including unhealthy diets, sedentary lifestyles, smoking and alcohol consumption. Countries without an integrated policy are mostly those that are least developed or in conflict, namely Djibouti, Libya, Somalia, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen. Jordan lacks an integrated policy 30,31 but monitors non-communicable diseases and related risk factors.

To address the increasing burden of non-communicable diseases, many Arab countries have developed multisectoral strategies or action plans for various diseases and common risk factors, including unhealthy diets, sedentary lifestyles, smoking and alcohol consumption. Countries without an integrated policy are mostly those that are least developed or in conflict, namely Djibouti, Libya, Somalia, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Yemen. Jordan lacks an integrated policy 30,31 but monitors non-communicable diseases and related risk factors. Imposing taxes on cigarettes:

all countries with data available38

have taxed cigarettes to reduce their affordability. Only four countries, namely,

Egypt,39 Jordan, Morocco and the

State of Palestine, have set the tax rate at equal to or more than 75 per cent

of the retail price, which is the rate proven effective in reducing demand for tobacco products.

Taxes work especially well in deterring the young, who are more sensitive than adults to price increases.

Imposing taxes on cigarettes:

all countries with data available38

have taxed cigarettes to reduce their affordability. Only four countries, namely,

Egypt,39 Jordan, Morocco and the

State of Palestine, have set the tax rate at equal to or more than 75 per cent

of the retail price, which is the rate proven effective in reducing demand for tobacco products.

Taxes work especially well in deterring the young, who are more sensitive than adults to price increases.

Banning smoking in public places: six countries, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya and the State of Palestine, have completely banned smoking in all public places. Other countries have partial or no bans. Compliance is mostly low to somewhat moderate.

Banning smoking in public places: six countries, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya and the State of Palestine, have completely banned smoking in all public places. Other countries have partial or no bans. Compliance is mostly low to somewhat moderate.

Introducing health warnings on cigarette packages: five countries (Djibouti, Egypt, Mauritania, Qatar and Saudi Arabia) require large health warnings on cigarette packages with specific characteristics.40 Saudi Arabia requires plain packaging, a policy

that scraps promotional, marketing and advertising features on tobacco packs. Other countries have introduced warnings that do not fully conform to appropriate criteria.

Introducing health warnings on cigarette packages: five countries (Djibouti, Egypt, Mauritania, Qatar and Saudi Arabia) require large health warnings on cigarette packages with specific characteristics.40 Saudi Arabia requires plain packaging, a policy

that scraps promotional, marketing and advertising features on tobacco packs. Other countries have introduced warnings that do not fully conform to appropriate criteria.

Banning tobacco advertising, promotion or sponsorship: several countries (Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen) have introduced bans on all forms of direct and indirect advertising. Others have bans that are not as comprehensive.

Banning tobacco advertising, promotion or sponsorship: several countries (Algeria, Bahrain, Djibouti, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen) have introduced bans on all forms of direct and indirect advertising. Others have bans that are not as comprehensive.

Implementing mass media campaigns: five countries (Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco, the State of Palestine and Tunisia) have recently41 implemented mass media campaigns to educate the public on the harmful effects of tobacco use and second-hand smoke for a minimum period of three weeks in line with specific standards.42 Other countries have undertaken media campaigns that do not completely follow these standards.

Implementing mass media campaigns: five countries (Bahrain, Jordan, Morocco, the State of Palestine and Tunisia) have recently41 implemented mass media campaigns to educate the public on the harmful effects of tobacco use and second-hand smoke for a minimum period of three weeks in line with specific standards.42 Other countries have undertaken media campaigns that do not completely follow these standards.

Improving access to tobacco cessation services: Qatar established a national help line to assist those seeking to quit smoking, along with an informative website and various options for nicotine replacement therapy. The anti-smoking programme of Saudi Arabia, offered in smoking clinics, resulted in nearly 30 per cent of participants successfully quitting smoking in 2019.43

Improving access to tobacco cessation services: Qatar established a national help line to assist those seeking to quit smoking, along with an informative website and various options for nicotine replacement therapy. The anti-smoking programme of Saudi Arabia, offered in smoking clinics, resulted in nearly 30 per cent of participants successfully quitting smoking in 2019.43

Several countries have developed a national digital health/e-health strategy or policy to institutionalize the use of information and communications technology for health and well-being. They include Bahrain, Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the Sudan.44 Oman has embedded its digital health strategy in its national health strategy. Progress in implementation varies among these countries.45

Several countries have developed a national digital health/e-health strategy or policy to institutionalize the use of information and communications technology for health and well-being. They include Bahrain, Egypt, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the Sudan.44 Oman has embedded its digital health strategy in its national health strategy. Progress in implementation varies among these countries.45 Telemedicine, a health-care service delivery tool, was used mostly by the private sector in various countries, including Egypt and Saudi Arabia, among others, for online consultations, patient referrals, diagnostics, and inpatient care and management.

Telemedicine, a health-care service delivery tool, was used mostly by the private sector in various countries, including Egypt and Saudi Arabia, among others, for online consultations, patient referrals, diagnostics, and inpatient care and management. Mobile applications, such as the Electronic

Mother and Child Health application (e-MCH) and the application for non-communicable diseases

(e-NCD), were used in Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and the Syrian Arab Republic for the diagnosis and management of patients.

Mobile applications, such as the Electronic

Mother and Child Health application (e-MCH) and the application for non-communicable diseases

(e-NCD), were used in Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine and the Syrian Arab Republic for the diagnosis and management of patients. Electronic contact tracing was used in Tunisia .

Electronic contact tracing was used in Tunisia . Electronic inventories and registries were deployed in the Sudan to support the home delivery of medicines, mainly to patients with non-communicable diseases.

Electronic inventories and registries were deployed in the Sudan to support the home delivery of medicines, mainly to patients with non-communicable diseases. The National E-health and Data Management Strategy (2016–2020) in Qatar, which sets standards and policies to improve the national e-health ecosystem, ensure the availability of high-quality digital health information and enhance patients’ safety and engagement in managing their health.

The National E-health and Data Management Strategy (2016–2020) in Qatar, which sets standards and policies to improve the national e-health ecosystem, ensure the availability of high-quality digital health information and enhance patients’ safety and engagement in managing their health.

The Health Sector Transformation Programme49 in Saudi Arabia, under its Vision 2030, which plans to restructure and digitize the health sector and enhance the quality of care by expanding e-health services.

A suite of applications, including Sehhaty, Seha, Mawid, Wasfaty and Tabaud, provides effective virtual programmes such as health consultations, specialized clinics and virtual home care services.

The Health Sector Transformation Programme49 in Saudi Arabia, under its Vision 2030, which plans to restructure and digitize the health sector and enhance the quality of care by expanding e-health services.

A suite of applications, including Sehhaty, Seha, Mawid, Wasfaty and Tabaud, provides effective virtual programmes such as health consultations, specialized clinics and virtual home care services.

Investment in technology and digital health infrastructure by the United Arab Emirates. Malaffi, a health information exchange platform initiated by the Department of Health in Abu Dhabi, now connects the entire health-care sector, linking 45,000 authorized users with hospitals and 2,000 public and private health-care facilities.

Investment in technology and digital health infrastructure by the United Arab Emirates. Malaffi, a health information exchange platform initiated by the Department of Health in Abu Dhabi, now connects the entire health-care sector, linking 45,000 authorized users with hospitals and 2,000 public and private health-care facilities.

Most countries continue to expand the capabilities of their health data collection and management systems. These efforts are critical

in fighting communicable and non-communicable diseases, and guiding evidence-based health programme planning and policymaking. The compilation of quality health data remains a challenge for several middle-income and least developed countries due to government coordination challenges, the fragmentation of health information systems, and low human and technical capacities. The following are some examples of efforts to enhance health data collection and management:

Most countries continue to expand the capabilities of their health data collection and management systems. These efforts are critical

in fighting communicable and non-communicable diseases, and guiding evidence-based health programme planning and policymaking. The compilation of quality health data remains a challenge for several middle-income and least developed countries due to government coordination challenges, the fragmentation of health information systems, and low human and technical capacities. The following are some examples of efforts to enhance health data collection and management:

Tunisia continues to increase the coverage of its information system on causes of death and to enhance the quality of registered data. Through collaboration with different partners and active data collection efforts, the rate of coverage increased from 40 per cent in 2017 to 61 per cent in 2020. Quality remains at a medium level, however; further efforts are needed to achieve intended results.50

Tunisia continues to increase the coverage of its information system on causes of death and to enhance the quality of registered data. Through collaboration with different partners and active data collection efforts, the rate of coverage increased from 40 per cent in 2017 to 61 per cent in 2020. Quality remains at a medium level, however; further efforts are needed to achieve intended results.50

The Ministry of Health of Libya , in collaboration with WHO, plans to improve its health information management by expanding district health information software to reach all municipalities.51 Nonetheless, further comprehensive reporting is needed, particularly in light of the absence of a national health data repository and standardized guidelines for data management and assessment. Financial constraints pose a significant challenge.

The Ministry of Health of Libya , in collaboration with WHO, plans to improve its health information management by expanding district health information software to reach all municipalities.51 Nonetheless, further comprehensive reporting is needed, particularly in light of the absence of a national health data repository and standardized guidelines for data management and assessment. Financial constraints pose a significant challenge.

A fragmented health information system was reported in Somalia until 2017, when district health information software was introduced for the collection, reporting and analysis of health data. A Health Information System Strategic

Plan for 2018–2022 addressed monitoring gaps. By 2021, reports indicated that the system was more updated and efficient in integrating disease surveillance, response mechanisms and public health alerts.

A fragmented health information system was reported in Somalia until 2017, when district health information software was introduced for the collection, reporting and analysis of health data. A Health Information System Strategic

Plan for 2018–2022 addressed monitoring gaps. By 2021, reports indicated that the system was more updated and efficient in integrating disease surveillance, response mechanisms and public health alerts.

Over the past decade, almost all countries52 have developed a standalone policy or plan and/or legislation on mental health or have integrated mental health into policies for general health,53 recognizing the importance of mental health as a right.

Over the past decade, almost all countries52 have developed a standalone policy or plan and/or legislation on mental health or have integrated mental health into policies for general health,53 recognizing the importance of mental health as a right. The National Plan for the Promotion of Mental Health (2017–2020) in Algeria, which focuses on strengthening the regulatory framework for mental health, training health personnel, developing mental health research and establishing a mental health information and communications system.57

The National Plan for the Promotion of Mental Health (2017–2020) in Algeria, which focuses on strengthening the regulatory framework for mental health, training health personnel, developing mental health research and establishing a mental health information and communications system.57

The Mental Health and Substance Use Prevention, Promotion and Treatment Strategy (2015–2020)

in Lebanon, which prioritizes strengthening mental health governance and the provision of mental health services in community based-settings for all, especially vulnerable groups. It underscores coordinated research on mental health and the implementation of activities to promote mental health and prevent substance abuse disorders.58

The Mental Health and Substance Use Prevention, Promotion and Treatment Strategy (2015–2020)

in Lebanon, which prioritizes strengthening mental health governance and the provision of mental health services in community based-settings for all, especially vulnerable groups. It underscores coordinated research on mental health and the implementation of activities to promote mental health and prevent substance abuse disorders.58

The provision of mental health support under primary health care in Bahrain to make mental health services more accessible and reduce stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues.

The provision of mental health support under primary health care in Bahrain to make mental health services more accessible and reduce stigma associated with seeking help for mental health issues.

The issuing of the first mental health law in 2019

(Law No.14) in Kuwait to improve treatment and rehabilitation and to protect individuals suffering from mental health issues.

The issuing of the first mental health law in 2019

(Law No.14) in Kuwait to improve treatment and rehabilitation and to protect individuals suffering from mental health issues.

The development of a national policy on mental health in the United Arab Emirates in 2019 to foster public and private efforts to promote comprehensive care, including preventive, curative and rehabilitative services. A mental health-care draft law was passed in 2021 to protect the rights of people who seek mental health care and to facilitate the rehabilitation of psychiatric patients into society.

The development of a national policy on mental health in the United Arab Emirates in 2019 to foster public and private efforts to promote comprehensive care, including preventive, curative and rehabilitative services. A mental health-care draft law was passed in 2021 to protect the rights of people who seek mental health care and to facilitate the rehabilitation of psychiatric patients into society.

Several Gulf Cooperation Council countries are initiating reforms to encourage private sector and foreign participation in health care. This transition59

marks a strategic shift from Governments being both investors and operators of health-care facilities to primarily focusing on strategic governance, planning and oversight, acting as policymakers and regulators. In tandem, private sector expertise and resources

are leveraged to meet growing health-care needs, including by significantly contributing to infrastructure development, efficiency, innovation and service quality as well as the production and distribution of medicines and health technologies. By emphasizing patient experiences, the private sector could also help position some Gulf Cooperation Council cities as global medical hubs. Examples of reforms to promote private sector and foreign participation include the following:

Several Gulf Cooperation Council countries are initiating reforms to encourage private sector and foreign participation in health care. This transition59

marks a strategic shift from Governments being both investors and operators of health-care facilities to primarily focusing on strategic governance, planning and oversight, acting as policymakers and regulators. In tandem, private sector expertise and resources

are leveraged to meet growing health-care needs, including by significantly contributing to infrastructure development, efficiency, innovation and service quality as well as the production and distribution of medicines and health technologies. By emphasizing patient experiences, the private sector could also help position some Gulf Cooperation Council cities as global medical hubs. Examples of reforms to promote private sector and foreign participation include the following:

Saudi Arabia introduced amendments to private health-care regulations. Resolution No. 683151 of 1436 H

(2015 G) opened the door for foreign parties to own hospitals, pharmacies and medical treatment centres in the kingdom, provided that they already operate health-care facilities outside Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia introduced amendments to private health-care regulations. Resolution No. 683151 of 1436 H

(2015 G) opened the door for foreign parties to own hospitals, pharmacies and medical treatment centres in the kingdom, provided that they already operate health-care facilities outside Saudi Arabia.

In the United Arab Emirates, Law No. 22 of 2015 was introduced to facilitate the regulation of partnerships between the public health system and the private sector in Dubai. A similar law in 2019 regulates public-private partnerships in Abu Dhabi. The operationalization

of both laws has faced delays and a lack of clear implementation procedures.

In the United Arab Emirates, Law No. 22 of 2015 was introduced to facilitate the regulation of partnerships between the public health system and the private sector in Dubai. A similar law in 2019 regulates public-private partnerships in Abu Dhabi. The operationalization

of both laws has faced delays and a lack of clear implementation procedures.

Arab middle-income countries face increasing

demand for health services from growing populations

and challenges in financing the sector. Health

systems confront the re-emergence of infectious

diseases in some cases as well as an increasing

burden from non-communicable diseases.

Middle-income countries have a relatively high share

of out-of-pocket health expenditure. All are above 30

per cent of current health expenses and, in some cases,

are as high as 55 per cent, such as in Egypt.60 Despite

reforms, significant inequalities in accessing affordable

treatments and paying for health-care services and

medications remain. Particularly vulnerable populations

include poor households, older persons, people with

chronic diseases, people with disabilities and refugees.

While middle-income countries have largely managed

to end epidemics of communicable diseases, they must

maintain and develop national programmes to closely

monitor, prevent and treat these diseases, some of which

have recurred among refugee populations. For example:

While middle-income countries have largely managed

to end epidemics of communicable diseases, they must

maintain and develop national programmes to closely

monitor, prevent and treat these diseases, some of which

have recurred among refugee populations. For example:

Facing one of the highest hepatitis C infection rates in

the world, Egypt in 2014 launched a nationwide initiative

(100 Million Healthy Lives) through which it tested

some 60 million high-risk people and treated some 4

million. This helped to bring down the infection rate

considerably. Egypt plans to sustain its efforts until the

epidemic is eradicated.61

Facing one of the highest hepatitis C infection rates in

the world, Egypt in 2014 launched a nationwide initiative

(100 Million Healthy Lives) through which it tested

some 60 million high-risk people and treated some 4

million. This helped to bring down the infection rate

considerably. Egypt plans to sustain its efforts until the

epidemic is eradicated.61

Jordan in 2020 established the National Epidemiology

and Infectious Diseases Centre to enhance the country’s

readiness to face emerging and re-emerging infectious

diseases. One priority for the Centre from 2023 to 2025

is to expand the availability and integration of highquality

monitoring data to guide national policymaking.62

Jordan in 2020 established the National Epidemiology

and Infectious Diseases Centre to enhance the country’s

readiness to face emerging and re-emerging infectious

diseases. One priority for the Centre from 2023 to 2025

is to expand the availability and integration of highquality

monitoring data to guide national policymaking.62

Morocco continues to increase resources for its

National Tuberculosis Control Programme, mobilizing

national and international partners around the

eradication of the disease. Tuberculosis continues

to take lives in Morocco due to social, economic and

environmental determinants of health that require

combined efforts under a multisectoral framework.63

Morocco continues to increase resources for its

National Tuberculosis Control Programme, mobilizing

national and international partners around the

eradication of the disease. Tuberculosis continues

to take lives in Morocco due to social, economic and

environmental determinants of health that require

combined efforts under a multisectoral framework.63 Middle-income countries are investing heavily to expand

health system infrastructure and workforces. For example:

Middle-income countries are investing heavily to expand

health system infrastructure and workforces. For example:

Morocco is upgrading its network of public hospitals,

allocating 1 billion dirhams annually since 2016. To

address its medical staffing deficit, it has increased

the budget allocated to the Ministry of Health to hire

more medical and paramedical personnel, including for

university hospital centres.64 Complementary efforts

are still needed to enhance the performance and

distribution of existing personnel.

Morocco is upgrading its network of public hospitals,

allocating 1 billion dirhams annually since 2016. To

address its medical staffing deficit, it has increased

the budget allocated to the Ministry of Health to hire

more medical and paramedical personnel, including for

university hospital centres.64 Complementary efforts

are still needed to enhance the performance and

distribution of existing personnel.

Rehabilitation of health infrastructure and the improved

availability of essential medications are top health sector priorities for the least developed countries and countries in

conflict. For example:

Rehabilitation of health infrastructure and the improved

availability of essential medications are top health sector priorities for the least developed countries and countries in

conflict. For example:

The National Development Programme for Post-War

Syria (Syria Strategic Plan 2030) in the Syrian Arab

Republic focuses on rebuilding medical facilities using

digital health maps that incorporate morbidity rates

and population density. The plan also aims to relocate

pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities to safe areas to

enhance national coverage.

The National Development Programme for Post-War

Syria (Syria Strategic Plan 2030) in the Syrian Arab

Republic focuses on rebuilding medical facilities using

digital health maps that incorporate morbidity rates

and population density. The plan also aims to relocate

pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities to safe areas to

enhance national coverage.

The Well and Healthy Libya: National Health Policy

2030 seeks to address systemic issues causing

shortages and limited access to medicines. The

availability of medicines in hospitals stands at 41

per cent, and at only 10 per cent in primary healthcare

centres and 13 per cent in warehouses.66 Libya

faces recurrent stockouts of vaccines, reproductive

health supplies and family planning medications,

and medicines to treat mental illnesses. The

implementation of related health reforms remains

heavily dependent on unified governance and

funding allocations.

The Well and Healthy Libya: National Health Policy

2030 seeks to address systemic issues causing

shortages and limited access to medicines. The

availability of medicines in hospitals stands at 41

per cent, and at only 10 per cent in primary healthcare

centres and 13 per cent in warehouses.66 Libya

faces recurrent stockouts of vaccines, reproductive

health supplies and family planning medications,

and medicines to treat mental illnesses. The

implementation of related health reforms remains

heavily dependent on unified governance and

funding allocations. International partners are increasingly major players

in supporting the least developed countries in

strengthening their national health systems and

enhancing access to health care, including for vulnerable

populations. For example:

International partners are increasingly major players

in supporting the least developed countries in

strengthening their national health systems and

enhancing access to health care, including for vulnerable

populations. For example: The Comoros received $30 million from the World Bank

in 2019 to strengthen its national health system and

improve primary health-care quality.67

The Comoros received $30 million from the World Bank

in 2019 to strengthen its national health system and

improve primary health-care quality.67 The World Bank granted $19.5 million in 2022 to

Djibouti for enhancing reproductive, maternal and child

health for both refugees and local communities.68

The World Bank granted $19.5 million in 2022 to

Djibouti for enhancing reproductive, maternal and child

health for both refugees and local communities.68

| The poor and uninsured (including the unemployed, self-employed individuals and those in the informal sector) face barriers in accessing health services, especially if they are not recipients of insurance or subsidized packages. This results in them shouldering the financial burden of out-of-pocket expenses to access medical care. | The Health Strategy (2018–2022) of Jordan broadened the scope of subsidized civil health insurance to include lowincome households (with an income between JD 300 and JD 500), a policy change that aims to enhance health-care accessibility and reduce financial barriers, ultimately striving for greater health equity.

In 2017, the Parliament of Morocco voted to expand national health coverage to include self-employed individuals and independent workers by 2025. This is expected to benefit approximately 11 million individuals, constituting about 30 per cent of the population. |

|

| Non-national residents and migrant workers often have limited access to fair and affordable healthcare services due to their employment status, lack of comprehensive health insurance and exclusion from formal health-care systems. This leads to difficulties in affording essential medications and high healthcare expenses that impose substantial financial burdens and increase vulnerability. | To extend health-care coverage to additional categories of workers in the United Arab Emirates, the Department of Health in Abu Dhabi introduced flexible health insurance packages in 2013. These were specifically designed for entrepreneurs and investors, aiming to provide them with health coverage at reduced and competitive costs, with options to upgrade if needed. | |

| Older persons , especially those living with one or more chronic illnesses, require long-term quality care. This increases the need for geriatric and gerontological education and training for health professionals and para-professionals. Shortages in most Arab countries are evident with a ratio of not more than 1 geriatrician for every 100,000 older persons. The lack of universal health protection hinders the provision of adequate medical care to older persons, negatively affecting their health and well-being. |

Egypt is working to advance training and research on geriatrics. The faculty of medicine in Ain Sham University offers a degree programme in geriatric medicine, involving theoretical training, a residency programme and a clinical training course.

a

Algeria and Jordan have taken steps to ensure health coverage for older persons. Law No. 10 of 2010 on the protection of older persons in Algeria grants free access to public health care to all persons aged 60 and above. In 2017, Jordan expanded subsidized health insurance coverage under its civil health insurance law to all persons aged 60 and above. b |

|

| Women and girls of childbearing age are subject to disproportionate health risks, including maternal mortality, unmet family planning needs and limited access to affordable contraceptives. Unmarried women, particularly in disadvantaged socioeconomic conditions, are at a higher risk of illegal abortions. Furthermore, services for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, including unintended pregnancies, remain limited. |

In Egypt, the Family Development Strategy (2015–2030) includes a dedicated pillar on improving access to family planning and reproductive health. The National Project for the Development of the Egyptian Family (2021–2023) aims to provide free and safe family planning and reproductive health services to women aged 18 to 45, including through the establishment of a family insurance fund to incentivize commitment to family planning. The project also seeks to strengthen penalties for child marriages, child labour and unregistered births.

Additionally, the Supporting Egyptian Women’s Health initiative, under “100 Million Healthy Lives”, intends to reach 28 million Egyptian women across the country, offering general reproductive health check-ups, early breast cancer detection and screenings for non-communicable diseases. |

|

| Persons with disabilities often encounter disparities in accessing equal health care due to physical barriers, discrimination, inaccessible information, high costs and insufficient policy support. | In the United Arab Emirates, the National Policy for Empowering Persons with Disabilities (2017) includes measures to improve health-care access and services, comprising fitness and wellness and physical and socioemotional well-being. The policy adopts an inclusive approach to integrating people with intellectual disabilities to ensure their full access to health-care services. | |

| Refugees and internally displaced persons face multiple barriers to health care, including a lack of awareness of available services and the cost of health consultations, treatment and medications. Formalization and documentation issues also hinder the health-care access of asylum seekers and irregular migrants, especially in fragile and conflict contexts. | Egypt grants refugees and asylum-seekers access to all health services provided in public facilities for free or at low cost, similar to Egyptian citizens. c | |

| People with HIV and AIDS are still at risk of stigma and discrimination, a lack of domestic investment in related health services and an absence of adequate information systems. | Jordan introduced its National Policy on HIV and AIDS and the World of Work in 2013. This policy prioritizes ensuring that employees living with HIV and AIDS access health care while maintaining the confidentiality and privacy of their HIV status and medical details. This creates an environment where employees can access health care without concerns of stigma or bias. The policy guarantees delivering appropriate medical treatment, care and support to HIV positive workers, including access to vital services such as antiretroviral therapy. | |

| People living in remote areas have limited access to reliable and quality health care, which increases their vulnerability to adverse health consequences. | In Algeria, an executive decree initiated an “institutional twinning” programme in 2016, connecting hospitals in the developed northern regions with those in the underdeveloped and remote southern areas of the country. The programme facilitates the sharing of resources, medical expertise and personnel to reduce health-care disparities, enhance healthcare access for residents in remote areas and provide healthcare services to underserved southern regions. | |

| Children and adolescents in the region are often at risk of being left behind when it comes to health equity and outcomes due to various factors, including economic disparities, a lack of access to quality health care and limited educational opportunities, especially related to their sexual and reproductive health. All these factors increase their vulnerability. | In Palestine, the 2016 School Health Policy aims to provide comprehensive health services to school-age children and adolescents. This includes regular health check-ups, vaccinations and health education programmes. The policy incorporates mental health support and counselling services within schools to address students’ psychological well-being, and promotes parental involvement in students’ health, fostering collaboration between schools and families. |

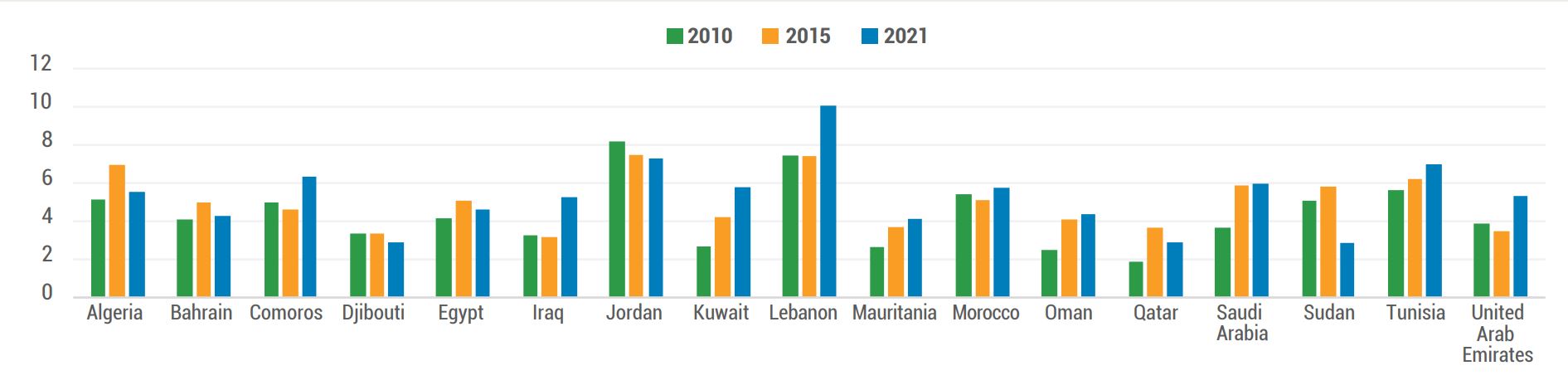

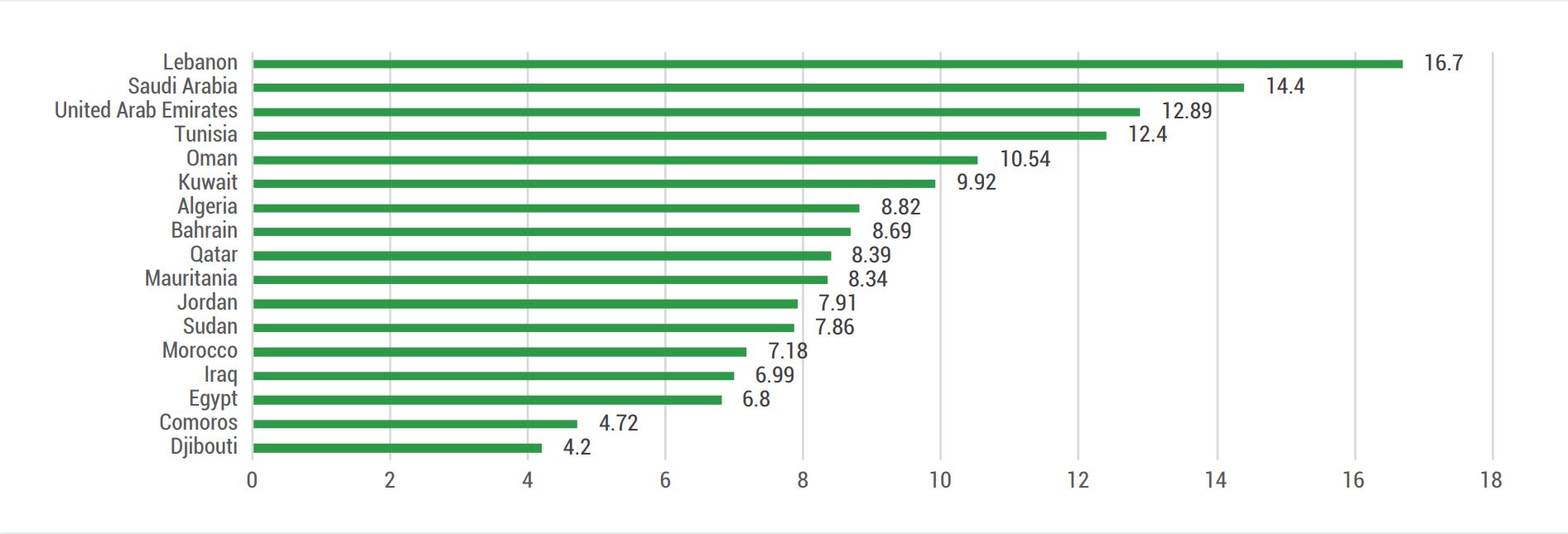

Source: WHO Global Health Observatory, Health Financing Indicators, accessed on 15 December 2023.

Source: WHO Global Health Observatory, Health Financing Indicators, accessed on 15 December 2023.

Source: WHO Global Health Expenditure Database, Data Explorer, Health Expenditure Data – Financing Schemes, accessed on 16 December 2023.

Source: WHO Global Health Expenditure Database, Data Explorer, Health Expenditure Data – Financing Schemes, accessed on 16 December 2023.

| Countries | Health financing transition | |

|---|---|---|

| Djibouti, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Oman, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates | Fast progress: there is an average annual increase in pooled health expenditures per capita and a decrease in out-of-pocket payments per capita, resulting in a rapid increase in the pooled share of health spending. | |

| Iraq, Morocco and Saudi Arabia | Slower progress: the rate of the annual increase in pooled health expenditures per capita is faster than that of out-of-pocket payments per capita, resulting in an increase in the pooled share of health spending, albeit at a slower pace than in the first category. | |

| Algeria, Bahrain and the Sudan | No progress: the rate of the annual increase in out-of-pocket payments per capita is faster than that of pooled health expenditures per capita, resulting in a decrease in the pooled share of health expenditure. | |

| Comoros | No progress: the rate of the annual decline in out-of-pocket payments per capita is faster than that of pooled health expenditures per capita. | |

Source: WHO Global Health Observatory, Health Financing Indicators, accessed on 15 December 2023;

Source: WHO Global Health Observatory, Health Financing Indicators, accessed on 15 December 2023;

1. Saleh and Fouad, 2022.

2. The four major non-communicable diseases are cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes and chronic respiratory disease.

3. See the World Bank data, Out-of-pocket expenditure as percentage of current health expenditure, accessed on 24 January 2024.

4. Several countries in the region have experienced prolonged conflict and political instability since 2011. These have severely disrupted health-care systems and disease surveillance and limited the ability to respond to public health emergencies.

5. WHO, 2023c.

6. Algeria, Bahrain, the Comoros, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya (the draft constitution adopted by the Constitution Drafting Assembly of Libya in July 2017), Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

7. Saudi Council of Health Insurance, Laws and Regulations.

8. Migrants mostly depend on individual or employer-sponsored private health insurance schemes.

9. Military personnel are insured by different schemes.

10. See Egypt, third Voluntary National Review 2021.

11. National Programme of Assistance to Needy Families.

12. See Les Comores, Tableau de la situation de l’égalité femme/homme.

13. See L’assurance maladie généralisée bientôt opérationnelle.

14. See Mauritania, Voluntary National Review 2019.

15. Katoue and others, 2022.

16. See Saudi Arabia, Voluntary National Review 2023.

17. See Algeria, Voluntary National Review 2019.

18. World Bank, 2020.

19. Integrated sexual and reproductive health packages should include family planning services, maternal and child health care, medical assistance to survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, post-abortion care, HIV prevention and management, other sexually transmitted infections, reproductive cancers and infertility.

20. WHO, 2020c. Exceptions include Somalia (less than 50 per cent) and Saudi Arabia and Yemen (less than 75 per cent). The 16 policy areas cover: family planning/contraception; sexually transmitted infections; cervical cancer prevention and control; antenatal care; childbirth; postnatal care; pre-term newborns; child health and development (includes seven subcategories); adolescent health and violence against women.

21. UNFPA and MENA Health Policy Forum, 2019.

22. Ibid.

23. Kabakian-Khasholian and others, 2020.

24. UNFPA and MENA Health Policy Forum, 2019.

25. Ibid.

26. UNFPA and MENA Health Policy Forum, 2018.

27. UNFPA and the American University of Beirut, Faculty of Health Sciences, Center for Public Health Practice, 2022.

28. Ibid.

29. According to UNFPA (2022), the region has 78,200 midwives; 130,000 more full-time midwives will be needed by 2030.

30. WHO, 2023a.

31. See the WHO Noncommunicable Diseases Data Portal, accessed on 12 December 2023.

32. See the Comoros, Voluntary National Review 2023.

33. World Bank, 2023.

34. See the United Nations Treaty Collection.

35. WHO, 2023e.

36. See Implementation Database for the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, Treaty provisions, General and other obligations, Comprehensive multisectoral national tobacco control strategy – C111, accessed on 23 October 2023.

37. WHO, 2023e.

38. No information has been reported for Djibouti, Somalia or the Syrian Arab Republic.

39. The tax rate in Egypt is 74.9 per cent of the retail price.

40. Relevant characteristics comprise: the inclusion of mandated and rotating health warnings on all cigarette packages and retail labelling, indications of the harmful consequences on health from tobacco use that are large, clear and visible and in all principle languages of a country, and pictures or pictograms. See the WHO Noncommunicable Diseases Data Portal, accessed on 12 December 2023.

41. Between July 2020 and June 2022.

42. An effective media campaign involves: (a) implementing the campaign as part of a comprehensive tobacco control programme; (b) forming a deep understanding of the target audience prior to the campaign through research; (c) pre-testing and refining communications materials for the campaign; (d) designing a rigorous media plan and process for purchasing air time and/or placement to ensure effective and efficient reach to the target audience; (e) working with journalists for publicity and coverage of the campaign; (f) evaluating the process after conclusion to assess implementation effectiveness; (g) evaluating outcomes to assess impact; and (h) airing the campaign on television and/or radio for a minimum of three weeks. See the WHO Noncommunicable Diseases Data Portal, accessed on 12 December 2023.

43. See the Ministry of Health Strategy (2020–2024).

44. WHO, 2022a.

45. WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA, 2022.

46. WHO, 2022a.

47. Lebanon, Ministry of Public Health, 2023.

48. WHO, 2022a.

49. See more on health sector transformation in Saudi Arabia under Vision 2030.

50. See Tunisia, Voluntary National Review 2021.

51. WHO, 2023

52. Libya, Oman and Somalia did not develop a policy or legislation on mental health. No data are available for the Comoros, Mauritania and the State of Palestine.

53. WHO, 2020b.

54. Only Egypt indicated that it had estimated and allocated human and financial resources for the implementation of its mental health plan launched in 2015. Although Lebanon did not indicate estimates and allocations, it noted that total government expenditure on mental health as a percentage of total government health expenditure was 5 per cent.

55. Lea Zeinoun, 2023.

56. WHO, 2020b.

57. See Algeria, Voluntary National Review 2019.

58. Lebanon, Ministry of Public Health, 2015.

59. Arab Health by Informa Markets, 2020.

60. See the WHO Global Health Expenditure database, accessed on 23 October 2023.

61. WHO, 2023d.

62. Jordan News, 2023.

64. See Morocco, Voluntary National Review 2020.

65. WHO Global Health Expenditure database, accessed on 23 October 2023.

66. United Nations Libya, Common Country Analysis, 2021.

67. World Bank, 2019.

68. World Bank, 2022.

69. See WHO data on health expenditure, accessed 15 December 2023.

70. ESCWA, 2022b.

71. Ibid.

72. Ibid.

73. Ibid.

74. UNICEF, 2018.

75. Ibid.

76. Ibid.

77. GCFF, 2022.

78. UNFPA and League of Arab States, 2020.

79. UNFPA, WHO and League of Arab States, 2022.

80. Bahrain News Agency, 2023.

81. See the extensive analysis of social determinants affecting the health of migrants globally and in the region as provided in WHO, 2022b.

Abdul Rahim, H., and others (2014). Non-communicable Diseases in the Arab World. The Lancet 383(9914): 356–367.

Arab Health by Informa Markets (2020). Healthcare and General Services in the GCC: The Road to a World-Class Healthcare System.

Atrache, S. (2021). Lebanon’s Deepening Crisis: The Case for a Sustainable Aid Response. Refugees International.

Bahrain News Agency (2023). Launching the Arab Health-Friendly Budgeting Strategy (Arabic). 21 May.

Bansal, D., and others (2023). A New One Health Framework in Qatar for Future Emerging and Re-emerging Zoonotic Diseases Preparedness and Response. One Health 16: 100487.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023). One Health Basics.

Dejong, J., and S. Abdallah Fahme (2021). COVID-19 and Gender in the Arab States: Using a human development lens to explore the gendered risks, outcomes, and impacts of the pandemic on women’s health.

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) (2018). Population and Development Report Issue No. 8: Prospects of Ageing with Dignity in the Arab Region.

__________ (2022a). Population and Development Report Issue No. 9: Building Forward Better for Older Persons in the Arab Region.

Abdul Rahim, H., and others (2014). Non-communicable Diseases in the Arab World. The Lancet 383(9914): 356–367.

Arab Health by Informa Markets (2020). Healthcare and General Services in the GCC: The Road to a World-Class Healthcare System.

Atrache, S. (2021). Lebanon’s Deepening Crisis: The Case for a Sustainable Aid Response. Refugees International.

Bahrain News Agency (2023). Launching the Arab Health-Friendly Budgeting Strategy (Arabic). 21 May.

Bansal, D., and others (2023). A New One Health Framework in Qatar for Future Emerging and Re-emerging Zoonotic Diseases Preparedness and Response. One Health 16: 100487.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023). One Health Basics.

Dejong, J., and S. Abdallah Fahme (2021). COVID-19 and Gender in the Arab States: Using a human development lens to explore the gendered risks, outcomes, and impacts of the pandemic on women’s health.

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) (2018). Population and Development Report Issue No. 8: Prospects of Ageing with Dignity in the Arab Region.

__________ (2022a). Population and Development Report Issue No. 9: Building Forward Better for Older Persons in the Arab Region.

__________ (2022b). Subsidized Health Insurance for the Hard-to-Reach – Towards Universal Health Coverage in the Arab Region: A First Look .

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA), and Economic Research Forum (2019). Rethinking Inequality in Arab Countries.

Global Concessional Financing Facility (GCFF) (2022). Annual Report 2021–2022.

Hyzam, D. (2022). Health Systems and the Changing Contexts of Wars in Arab Countries. Arab NGO Network for Development.

Jordan News (2023). National epidemiology center rolls out 2023–2025 strategy. 16 January.

Kabakian-Khasholian, T., and others (2020). Integration of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in the Provision of Primary Health Care in the Arab States: Status and a Way Forward. Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 28(2): 1773693.

Katoue, M. G., and others (2022). Healthcare System Development in the Middle East and North Africa Region: Challenges, Endeavors and Prospective Opportunities. Front Public Health.

Kronfol, N. M. (2012). Delivery of Health Services in Arab Countries: A Review. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal 18(12): 1229–1238.

Lebanon, Ministry of Public Health (2015). Mental Health and Substance Use Prevention, Promotion and Treatment Strategy for Lebanon 2015–2020.

__________ (2023). Empowering Lebanon’s Healthcare System: A Vision for Digital Health Transformation.

Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) (2023). Gaza: UN expert condemns ‘unrelenting war’ on health system amid airstrikes on hospitals and health workers. Press release, 7 December.

Saleh, S., and F. Fouad (2022). Political Economy of Health in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Regions in the Middle East and North Africa Region. Journal of Global Health 12: 01003.

Sharek (2023). Health Ministry formulates national plan to implement ‘One Health Approach’. 11 July.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2018). Immunization Financing in MENA Middle Income Countries.

__________ (2021). Situational Analysis of Women and Girls in the Middle East and North Africa: A Decade Review 2010–2020.

United Nations News (2024). Nearly 600 attacks on healthcare in Gaza and the West Bank since war began: WHO. 5 January.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (2022). The State of Midwifery Workforce in the Arab Region.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and League of Arab States (2020). Multi-sectoral Arab Strategy for Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health 2019–2030.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and MENA Health Policy Forum (2017). Policy Brief: Integration of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services in the Arab States Region: A Six-Country Assessment.

__________ (2018). Mapping of Population Policies in the Arab Region and Their Alignment with Existing Strategies in Relation to the ICPD: Findings from 10 Countries.

__________ (2019). Policy Brief on the Integration of Sexual and Reproductive Health Services into Primary Health Care in the Arab States Region: Assessment of Eleven Arab Countries.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), and the American University of Beirut, Faculty of Health Sciences, Center for Public Health Practice (2022). Youth Sexual and Reproductive Health and Reproductive Rights in the Arab Region: An Overview.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), World Health Organization (WHO), and League of Arab States (2022). Arab Strategy to Promote Nursing and Midwifery (Arabic).

University of California Berkeley (2023). Research Snapshot: The Impact of Attacks on Syrian Health Systems. Research for Health in Humanitarian Crises.

World Bank (2019). World Bank supports Comoros to improve primary health care.

__________ (2020). Improving Primary Health in Rural Areas and Responding to COVID-19 Pandemic Emergency. Kingdom of Morocco.

__________ (2022). Djibouti: new financing to strengthen health and nutrition services. 29 May.

__________ (2023). The Gulf Economic Update Report: The Health and Economic Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases in the GCC.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018). Framework for Action for Health Workforce Development in the Eastern Mediterranean Region 2017–2030. WHO-EM/HRH/640/E.

__________ (2020a). Health workforce snapshot: Jordan.

__________ (2020b). Mental Health Atlas 2020. Country profiles.

__________ (2020c). Sexual, Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, and Adolescent Health Policy Survey, 2018–2019.

__________ (2022a). Regional Strategy for Fostering Digital Health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (2023–2027). EM/RC69/8. Sixty-ninth Session of the Regional Committee for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, 10–13 October.

__________ (2022b). World Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants.

__________ (2023a). Assessing National Capacity for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases: Report of the 2019 Country Capacity Survey in the Eastern Mediterranean Region.

__________ (2023b). Health workforce management systems.

__________ (2023c). Progress on the Health-Related Sustainable Development Goals and Targets in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 2023.

__________ (2023d). WHO Commends Egypt for Its Progress on the Path to Eliminate Hepatitis C. 9 October.

__________ (2023e). WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2023: Protect People from Tobacco Smoke.

__________ (2023f). WHO Country Office, Libya: Annual Report 2022. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean.

World Health Organization (WHO), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) (2022). Mapping of Digital Health Tools and Technologies: Oman Country Brief.

Zeinoun, L. (2023). Understanding Mental Health in the Arab Region: Challenges and Barriers to Accessing the Right to Mental Health. An input into the 2023 Arab Watch Report: The Right to Health, Arab NGO Network for Development.