Water scarcity poses formidable challenges to achieving water security and sustainable development in the Arab region, with far-reaching implications for food and energy security, economic progress, livelihoods and human health. Given the gravity of the situation, the region’s progress so far on SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) remains insufficient. Access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services is uneven both among and within countries. Furthermore, water-use efficiency has regressed, and freshwater withdrawals have soared to highly unsustainable levels. More efforts are needed to implement integrated water resource management (IWRM), including through transboundary water cooperation. The region’s pursuit of SDG 6 is also challenged by climate change and a lack of adequate financing. Notably, official development assistance directed to sustainable water management has declined, underscoring the urgent need for renewed commitment and investment in WASH-related initiatives.

Most Arab States have acknowledged water and sanitation as human rights at the regional and global levels, but only some have explicitly recognized these rights in their legal frameworks. As at April 2023, 18 States1 had ratified the Arab Charter on Human Rights, which includes the provision of safe drinking water and proper sanitation systems among the measures States should take to ensure rights to an adequate standard of living and a healthy environment. Twenty Arab States2 voted in favour of the United Nations General Assembly resolution 64/292 on the human right to water and sanitation in 2010. Yet only four countries – Egypt, Morocco, Somalia and Tunisia – have explicitly recognized the rights to water, sanitation or both in their constitutions. At least five other countries – Algeria, the Comoros, Lebanon, Mauritania and the State of Palestine – have explicitly recognized these rights elsewhere in their legislations.

Most Arab States have acknowledged water and sanitation as human rights at the regional and global levels, but only some have explicitly recognized these rights in their legal frameworks. As at April 2023, 18 States1 had ratified the Arab Charter on Human Rights, which includes the provision of safe drinking water and proper sanitation systems among the measures States should take to ensure rights to an adequate standard of living and a healthy environment. Twenty Arab States2 voted in favour of the United Nations General Assembly resolution 64/292 on the human right to water and sanitation in 2010. Yet only four countries – Egypt, Morocco, Somalia and Tunisia – have explicitly recognized the rights to water, sanitation or both in their constitutions. At least five other countries – Algeria, the Comoros, Lebanon, Mauritania and the State of Palestine – have explicitly recognized these rights elsewhere in their legislations.

Access to safe drinking water has been integrated into the policies of most Arab countries. Yet measures tailored to the specific needs of vulnerable populations remain less common. Among 19 countries surveyed,3 all had adopted policies or plans to ensure access to safely managed drinking water, although some are now outdated and require updating to factor in water scarcity and climate change risks. Most countries (18 out of 20)4 have established national drinking water quality standards, which water utilities, government agencies and other stakeholders use to monitor and manage the quality of drinking water. Several countries5 (12 out of 18) have incorporated water safety plans or equivalent risk management approaches into their policies

or regulations. For example, the Updated National Water Sector Strategy (2020) of Lebanon includes a water safety plan manual, and the Electricity and Water Authority in Bahrain has a contingency and disaster plan.

Access to safe drinking water has been integrated into the policies of most Arab countries. Yet measures tailored to the specific needs of vulnerable populations remain less common. Among 19 countries surveyed,3 all had adopted policies or plans to ensure access to safely managed drinking water, although some are now outdated and require updating to factor in water scarcity and climate change risks. Most countries (18 out of 20)4 have established national drinking water quality standards, which water utilities, government agencies and other stakeholders use to monitor and manage the quality of drinking water. Several countries5 (12 out of 18) have incorporated water safety plans or equivalent risk management approaches into their policies

or regulations. For example, the Updated National Water Sector Strategy (2020) of Lebanon includes a water safety plan manual, and the Electricity and Water Authority in Bahrain has a contingency and disaster plan.

The Drinking Water Safety Strategic Framework (2017) adopted by the Sudan aims to ensure that everyone has sustainable access to safe drinking water, helping to uphold the human right to water and a range of other human rights. The framework has four strategic objectives: to protect water sources from pollution and ensure they are sustainably managed; to design and build water supply systems that are resilient to climate change and other challenges; to strengthen management processes to ensure water supply systems are properly operated and maintained; and to strengthen monitoring and surveillance systems so that drinking water is consistently safe. The framework was developed through a consultative process involving the Government, stakeholders and development partners, and is aligned with international standards and best practices.

The Drinking Water Safety Strategic Framework (2017) adopted by the Sudan aims to ensure that everyone has sustainable access to safe drinking water, helping to uphold the human right to water and a range of other human rights. The framework has four strategic objectives: to protect water sources from pollution and ensure they are sustainably managed; to design and build water supply systems that are resilient to climate change and other challenges; to strengthen management processes to ensure water supply systems are properly operated and maintained; and to strengthen monitoring and surveillance systems so that drinking water is consistently safe. The framework was developed through a consultative process involving the Government, stakeholders and development partners, and is aligned with international standards and best practices.

The Jordanian Standard No. 286 (2015), published by the Jordan Standards and Metrology Organization, specifies requirements for the quality of drinking water. It covers a wide range of parameters, including microbiological, physical and chemical, and specifies sampling and testing methods to guarantee compliance. The standard is aligned with international standards, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality, and is used by water utilities, government agencies and other stakeholders to monitor and manage the quality of drinking water. Notably, the standard requires water utilities to provide consumers with information about the quality of their drinking water.

The Jordanian Standard No. 286 (2015), published by the Jordan Standards and Metrology Organization, specifies requirements for the quality of drinking water. It covers a wide range of parameters, including microbiological, physical and chemical, and specifies sampling and testing methods to guarantee compliance. The standard is aligned with international standards, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality, and is used by water utilities, government agencies and other stakeholders to monitor and manage the quality of drinking water. Notably, the standard requires water utilities to provide consumers with information about the quality of their drinking water.

Most countries have adopted policies on safely managed sanitation services but have not done enough to ensure equitable access in rural and urban areas. Among the 16 surveyed countries,6 all had national policies covering both urban and rural sanitation. While a majority7 (15 out of 17) have wastewater treatment standards, fewer countries8 (11 out of 16) have standards for faecal sludge management. Only 3 out of 15 countries –Egypt, Oman and Tunisia – have adopted sanitation safety plans for local risk assessment and management, significantly less than the 12 countries with safety plans for drinking water services.

Most countries have adopted policies on safely managed sanitation services but have not done enough to ensure equitable access in rural and urban areas. Among the 16 surveyed countries,6 all had national policies covering both urban and rural sanitation. While a majority7 (15 out of 17) have wastewater treatment standards, fewer countries8 (11 out of 16) have standards for faecal sludge management. Only 3 out of 15 countries –Egypt, Oman and Tunisia – have adopted sanitation safety plans for local risk assessment and management, significantly less than the 12 countries with safety plans for drinking water services.

The Sanitation Code (2012) of Tunisia is a stand-out example of a comprehensive and advanced sanitation code. It covers the planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance of sanitation systems, along with the financing of sanitation services and the monitoring and enforcement of sanitation regulations. It also delineates the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders. Since its adoption, Tunisia has made significant strides in sanitation access, with the proportion of the population with access to safely managed sanitation rising from 69.5 per cent in 2012 to 81 per cent in 2022. Rural and urban disparities have narrowed, closing the access gap from 43.5 percentage points in 2012 to 26 percentage points in 2022.

The Sanitation Code (2012) of Tunisia is a stand-out example of a comprehensive and advanced sanitation code. It covers the planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance of sanitation systems, along with the financing of sanitation services and the monitoring and enforcement of sanitation regulations. It also delineates the roles and responsibilities of various stakeholders. Since its adoption, Tunisia has made significant strides in sanitation access, with the proportion of the population with access to safely managed sanitation rising from 69.5 per cent in 2012 to 81 per cent in 2022. Rural and urban disparities have narrowed, closing the access gap from 43.5 percentage points in 2012 to 26 percentage points in 2022.

Most countries have adopted policies to ensure the affordability of WASH services. In parallel, to address overconsumption and enhance the financial sustainability of utilities, some countries are pursuing reforms to restructure tariffs and improve cost recovery.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, most people connected to piped networks in the region are billed for services. As of mid-2015, at least 15 countries9 used volumetric tariff rates for drinking water. In addition, two countries – Lebanon and the Sudan – applied flat tariffs. For sanitation, 13 countries10 had volumetric tariff rates, 3 (Lebanon, the State of Palestine and the Sudan) had flat tariffs and 2 (Qatar and Saudi Arabia) offered free services. Since then, Saudi Arabia has introduced a tariff for wastewater treatment and Qatar has started charging a fee for non-Qatari residents and establishments.

Most countries have adopted policies to ensure the affordability of WASH services. In parallel, to address overconsumption and enhance the financial sustainability of utilities, some countries are pursuing reforms to restructure tariffs and improve cost recovery.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, most people connected to piped networks in the region are billed for services. As of mid-2015, at least 15 countries9 used volumetric tariff rates for drinking water. In addition, two countries – Lebanon and the Sudan – applied flat tariffs. For sanitation, 13 countries10 had volumetric tariff rates, 3 (Lebanon, the State of Palestine and the Sudan) had flat tariffs and 2 (Qatar and Saudi Arabia) offered free services. Since then, Saudi Arabia has introduced a tariff for wastewater treatment and Qatar has started charging a fee for non-Qatari residents and establishments. In 2015, Saudi Arabia implemented a revised water tariff structure,

a first step towards gradually removing subsidies and meeting the goal of Saudi Vision 2030 of achieving full cost recovery. Under the new tariff structure, the price for monthly volumes under 15 cubic metres remained unchanged while tariffs for higher volumes increased significantly. For instance, the price for 50 cubic metres of water rose 16 times, from $1.35 to $21.79, while for 100 cubic metres, it climbed 29 times, from $3.35 to $96.46. The tariff reform also introduced wastewater and metre fees for the first time, leading to a further increase in the combined monthly bill for WASH services. The new tariff was designed to enhance cost recovery to 30 per cent of the estimated marginal cost of water, up from an estimated pre-reform level of 7

per cent. Due to significant public backlash against the new system, the Government decided to suspend further tariff hikes required to meet 100 per cent cost recovery.

In 2015, Saudi Arabia implemented a revised water tariff structure,

a first step towards gradually removing subsidies and meeting the goal of Saudi Vision 2030 of achieving full cost recovery. Under the new tariff structure, the price for monthly volumes under 15 cubic metres remained unchanged while tariffs for higher volumes increased significantly. For instance, the price for 50 cubic metres of water rose 16 times, from $1.35 to $21.79, while for 100 cubic metres, it climbed 29 times, from $3.35 to $96.46. The tariff reform also introduced wastewater and metre fees for the first time, leading to a further increase in the combined monthly bill for WASH services. The new tariff was designed to enhance cost recovery to 30 per cent of the estimated marginal cost of water, up from an estimated pre-reform level of 7

per cent. Due to significant public backlash against the new system, the Government decided to suspend further tariff hikes required to meet 100 per cent cost recovery.

Freshwater resources remain a key component of national efforts to achieve water security, with policies focusing on developing and managing supplies and protecting resources. An increasing number of countries are prioritizing resource conservation and preservation. For example, the constitutions of Algeria (2016) and Tunisia (2022) have codified the safeguarding of water resources for future generations. Several countries, including Algeria, Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen, have regulations to curtail extraction, such

as quotas, volumetric pricing, drilling licenses and protection zones. For example, Bahrain ceased groundwater withdrawal in 2016, designating

it as an emergency reserve. Some countries have embraced advanced technologies, such as remote sensing, for enhanced water monitoring and management. For instance, Jordan employs remote sensing to track well development, estimate water use and detect illegal abstraction, while Bahrain uses the Internet of things to automate irrigation systems. Some countries have taken steps towards decentralization and local governance, as is the case for aquifer contracts in Morocco, local agricultural development groups in Tunisia, and local water corporations and autonomous utilities in Yemen.

Freshwater resources remain a key component of national efforts to achieve water security, with policies focusing on developing and managing supplies and protecting resources. An increasing number of countries are prioritizing resource conservation and preservation. For example, the constitutions of Algeria (2016) and Tunisia (2022) have codified the safeguarding of water resources for future generations. Several countries, including Algeria, Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen, have regulations to curtail extraction, such

as quotas, volumetric pricing, drilling licenses and protection zones. For example, Bahrain ceased groundwater withdrawal in 2016, designating

it as an emergency reserve. Some countries have embraced advanced technologies, such as remote sensing, for enhanced water monitoring and management. For instance, Jordan employs remote sensing to track well development, estimate water use and detect illegal abstraction, while Bahrain uses the Internet of things to automate irrigation systems. Some countries have taken steps towards decentralization and local governance, as is the case for aquifer contracts in Morocco, local agricultural development groups in Tunisia, and local water corporations and autonomous utilities in Yemen.

Non-conventional water resources, particularly desalinated

water and treated wastewater, play a pivotal role in the water

policies and plans of Gulf Cooperation Council countries and are gaining significance in other countries.

An increasing number of countries are incorporating desalination into their water strategies. Since the 1970s, Gulf Cooperation Council countries have placed a strong emphasis on large-scale projects, advanced technologies and regulatory frameworks to ensure water quality and safety. More recently, some middle-income and least developed countries have also adopted water desalination policy frameworks, although typically at a different scale and level of investment compared to the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. As of 2020, a total of 133 water desalination plants were operational or under construction in Algeria, Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia.13

Non-conventional water resources, particularly desalinated

water and treated wastewater, play a pivotal role in the water

policies and plans of Gulf Cooperation Council countries and are gaining significance in other countries.

An increasing number of countries are incorporating desalination into their water strategies. Since the 1970s, Gulf Cooperation Council countries have placed a strong emphasis on large-scale projects, advanced technologies and regulatory frameworks to ensure water quality and safety. More recently, some middle-income and least developed countries have also adopted water desalination policy frameworks, although typically at a different scale and level of investment compared to the Gulf Cooperation Council countries. As of 2020, a total of 133 water desalination plants were operational or under construction in Algeria, Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia.13

The Water Substitution and Reuse Policy (2016) of Jordan seeks

to direct the water sector towards more efficiency by promoting the use of treated wastewater in irrigation and other economic activities, thus freeing fresh water for municipal uses. The policy calls for expanding wastewater collection and treatment, updating quality standards, promoting decentralized treatment systems for smaller locations, and targeting awareness and educational programmes

to farmers.

The Water Substitution and Reuse Policy (2016) of Jordan seeks

to direct the water sector towards more efficiency by promoting the use of treated wastewater in irrigation and other economic activities, thus freeing fresh water for municipal uses. The policy calls for expanding wastewater collection and treatment, updating quality standards, promoting decentralized treatment systems for smaller locations, and targeting awareness and educational programmes

to farmers.

The Water Conservation Strategy (2010) of the United Arab Emirates calls for the efficient management and better use of desalinated water and treated wastewater, including by applying economic optimization principles to the design of future desalination plants, further developing aquifer storage and recovery by using surplus desalinated water, coordinating measures to increase the use of treated wastewater and conducting awareness-raising campaigns

to overcome public concerns. In addition, the UAE Water Security Strategy 2036 (2017) calls for expanding the use of treated wastewater by 95 per cent by 2050.

The Water Conservation Strategy (2010) of the United Arab Emirates calls for the efficient management and better use of desalinated water and treated wastewater, including by applying economic optimization principles to the design of future desalination plants, further developing aquifer storage and recovery by using surplus desalinated water, coordinating measures to increase the use of treated wastewater and conducting awareness-raising campaigns

to overcome public concerns. In addition, the UAE Water Security Strategy 2036 (2017) calls for expanding the use of treated wastewater by 95 per cent by 2050.

Water-use efficiency and conservation measures are increasingly included in water policies and plans across the region, with a notable emphasis on the agricultural sector. Recognizing the critical role of agriculture, which accounts for over 80 per cent of freshwater withdrawals in the region,17 and guided by a water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus perspective, most countries have embraced policies to enhance water-use efficiency in this sector. These policies include the promotion of precision irrigation (implemented in most countries)18, the adoption of water-efficient cropping systems (prevalent in several countries)19 and the enhancement of water metering (evident in some countries)20. Some countries have also sought to limit the volume of water used in agriculture. For example, the Water Reallocation Policy adopted by Jordan caps irrigation water volumes and redistributes water to municipal water use and other sectors, while the National Transformation Programme of Saudi Arabia seeks to reduce the percentage of water used in agriculture relative to total available water resources.

Water-use efficiency and conservation measures are increasingly included in water policies and plans across the region, with a notable emphasis on the agricultural sector. Recognizing the critical role of agriculture, which accounts for over 80 per cent of freshwater withdrawals in the region,17 and guided by a water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus perspective, most countries have embraced policies to enhance water-use efficiency in this sector. These policies include the promotion of precision irrigation (implemented in most countries)18, the adoption of water-efficient cropping systems (prevalent in several countries)19 and the enhancement of water metering (evident in some countries)20. Some countries have also sought to limit the volume of water used in agriculture. For example, the Water Reallocation Policy adopted by Jordan caps irrigation water volumes and redistributes water to municipal water use and other sectors, while the National Transformation Programme of Saudi Arabia seeks to reduce the percentage of water used in agriculture relative to total available water resources.

Bahrain has made significant strides in reducing its water stress level from 249 per cent of renewable freshwater resources in 2000 to 134 per cent in 2020. This improvement can be attributed to several key factors, including increased use of desalinated water and treated wastewater resources, the adoption of more efficient irrigation technologies, the implementation of smart metering and a shift towards less water-intensive sectors. While the water stress level in 2020 remained above the regional average of 120 per cent and was significantly higher than the global average of 18 per cent, the country stands out for achieving the most rapid reduction in water stress in the region in the last two decades. It is one of only five Arab countries to have successfully lowered its water stress levels since 2000.

Bahrain has made significant strides in reducing its water stress level from 249 per cent of renewable freshwater resources in 2000 to 134 per cent in 2020. This improvement can be attributed to several key factors, including increased use of desalinated water and treated wastewater resources, the adoption of more efficient irrigation technologies, the implementation of smart metering and a shift towards less water-intensive sectors. While the water stress level in 2020 remained above the regional average of 120 per cent and was significantly higher than the global average of 18 per cent, the country stands out for achieving the most rapid reduction in water stress in the region in the last two decades. It is one of only five Arab countries to have successfully lowered its water stress levels since 2000. Some progress has been made in the adoption of policies to promote IWRM. Further measures are needed to build capacity, bolster institutions and increase investment. IWRM improved in most Arab countries between 2017 and 2020. Oman stands out for more than doubling IWRM implementation in this period, demonstrating that substantial and rapid progress can be achieved.21 In most countries, IWRM policies, laws or plans are in place at the national level but more efforts are needed to transfer capacity and knowledge to local levels.22 Some countries have created cross-sectoral coordination frameworks, such as the National Agency for Integrated Water Resources Management in Algeria and the High Council for Water and Climate in Morocco.

Some progress has been made in the adoption of policies to promote IWRM. Further measures are needed to build capacity, bolster institutions and increase investment. IWRM improved in most Arab countries between 2017 and 2020. Oman stands out for more than doubling IWRM implementation in this period, demonstrating that substantial and rapid progress can be achieved.21 In most countries, IWRM policies, laws or plans are in place at the national level but more efforts are needed to transfer capacity and knowledge to local levels.22 Some countries have created cross-sectoral coordination frameworks, such as the National Agency for Integrated Water Resources Management in Algeria and the High Council for Water and Climate in Morocco.

The National Environmental Strategy and Action Plan for Iraq (2013–2017) calls for the negotiation of agreements governing riparian rights, the exchange of operational and hydraulic information and the implementation of joint hydraulic projects with neighbouring countries.

The National Environmental Strategy and Action Plan for Iraq (2013–2017) calls for the negotiation of agreements governing riparian rights, the exchange of operational and hydraulic information and the implementation of joint hydraulic projects with neighbouring countries. While all Arab countries mention climate change in their water policies or strategies, more specific and concrete adaptation measures are needed. Water adaptation measures have been prioritized in the nationally determined contributions of 20 Arab countries and further detailed in the national adaptation plans of 3 countries (Kuwait, the State of Palestine and the Sudan). Additionally, 12 out of 16 Arab countries24 have integrated climate change preparedness for WASH into their national planning, covering mitigation, adaptation and the resilience of drinking water systems. In their water and climate policies and strategies, however, most countries only partially address water scarcity and climate risks to water. Jordan, the State of Palestine and Tunisia are notable exceptions, having developed policy instruments that comprehensively address these critical challenges.

While all Arab countries mention climate change in their water policies or strategies, more specific and concrete adaptation measures are needed. Water adaptation measures have been prioritized in the nationally determined contributions of 20 Arab countries and further detailed in the national adaptation plans of 3 countries (Kuwait, the State of Palestine and the Sudan). Additionally, 12 out of 16 Arab countries24 have integrated climate change preparedness for WASH into their national planning, covering mitigation, adaptation and the resilience of drinking water systems. In their water and climate policies and strategies, however, most countries only partially address water scarcity and climate risks to water. Jordan, the State of Palestine and Tunisia are notable exceptions, having developed policy instruments that comprehensively address these critical challenges.

The National Water Strategy (2023–2040) of Jordan underscores the water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus with well-defined targets and objectives. It advocates the integration of renewable energy in the water sector and enhanced synergy between water and agriculture activities, with a focus on optimizing the productivity of irrigation water.

The National Water Strategy (2023–2040) of Jordan underscores the water-energy-food-ecosystem nexus with well-defined targets and objectives. It advocates the integration of renewable energy in the water sector and enhanced synergy between water and agriculture activities, with a focus on optimizing the productivity of irrigation water. The National Water Policy for Palestine intends to develop flexible strategies to address climate change impacts on water resources, limit the water sector’s carbon footprint and reduce the water footprint through the most efficient use.

The National Water Policy for Palestine intends to develop flexible strategies to address climate change impacts on water resources, limit the water sector’s carbon footprint and reduce the water footprint through the most efficient use.

Source:ESCWA, 2023b.

Source:ESCWA, 2023b.

Source:ESCWA, 2023b.

Source:ESCWA, 2023b.

Arab least developed countries are making significant strides to eradicate open defecation, prioritizing behaviour modification initiatives, communal toilet construction and targeted assistance for vulnerable populations. Five out of six countries – Djibouti, Mauritania, Somalia, the Sudan and Yemen – have policies or plans to tackle open defecation. The Comoros stands out for its remarkably low incidence of the practice.27

Arab least developed countries are making significant strides to eradicate open defecation, prioritizing behaviour modification initiatives, communal toilet construction and targeted assistance for vulnerable populations. Five out of six countries – Djibouti, Mauritania, Somalia, the Sudan and Yemen – have policies or plans to tackle open defecation. The Comoros stands out for its remarkably low incidence of the practice.27

The WASH Sector Strategic Plan (2019–2023) of Somalia prioritizes a number of goals for improving sanitation, including ending open defecation. It seeks to increase the number of villages free of open defecation from a baseline of 144 in 2018 to 4,068 in 2023. Moreover, it establishes a target to raise the percentage of people living in environments free from open defecation to 70 per cent by 2023.

The WASH Sector Strategic Plan (2019–2023) of Somalia prioritizes a number of goals for improving sanitation, including ending open defecation. It seeks to increase the number of villages free of open defecation from a baseline of 144 in 2018 to 4,068 in 2023. Moreover, it establishes a target to raise the percentage of people living in environments free from open defecation to 70 per cent by 2023. The National Roadmap to End Open Defecation in the Sudan outlines a comprehensive approach including sanitation marketing, tailored toilet designs, community certification, innovative financing and enhanced coordination mechanisms.

The National Roadmap to End Open Defecation in the Sudan outlines a comprehensive approach including sanitation marketing, tailored toilet designs, community certification, innovative financing and enhanced coordination mechanisms. Arab least developed countries are increasingly enacting policies that promote the integration of traditional knowledge and practices as well as modern approaches for sustainable water management in livestock production. The livestock sector is very important to the economies of most least developed countries, providing food, income and employment for millions of people. The sector is also a major user of water and highly vulnerable to climate change. As a result, water policies for sustainable livestock production focus on water access and conservation, climate change adaptation and sustainable grazing practices.

Arab least developed countries are increasingly enacting policies that promote the integration of traditional knowledge and practices as well as modern approaches for sustainable water management in livestock production. The livestock sector is very important to the economies of most least developed countries, providing food, income and employment for millions of people. The sector is also a major user of water and highly vulnerable to climate change. As a result, water policies for sustainable livestock production focus on water access and conservation, climate change adaptation and sustainable grazing practices.

The National Adaptation Plan of the Sudan outlines various adaptation measures related to water and rangelands, including enhanced water harvesting techniques, the rehabilitation of hafirs and dams, support for irrigated fodder crops and encouragement of the use of smaller livestock breeds adapted to drought conditions.

The National Adaptation Plan of the Sudan outlines various adaptation measures related to water and rangelands, including enhanced water harvesting techniques, the rehabilitation of hafirs and dams, support for irrigated fodder crops and encouragement of the use of smaller livestock breeds adapted to drought conditions. The National Strategy for Sustainable Access to Water and Sanitation of Mauritania intends to improve access to water for livestock by carrying out an inventory of existing pastoral water points and creating 600 new ones by 2030.

The National Strategy for Sustainable Access to Water and Sanitation of Mauritania intends to improve access to water for livestock by carrying out an inventory of existing pastoral water points and creating 600 new ones by 2030. Regulations and standards for the sanitation chain remain limited. Among five surveyed least developed countries, three (the Comoros, the Sudan and Yemen) have policy instruments on wastewater treatment. Notably, Yemen is the only one among them with policies or plans for the safe use of treated wastewater. Only Somalia among these countries has enacted regulations, standards or guidelines addressing faecal sludge treatment.28

Regulations and standards for the sanitation chain remain limited. Among five surveyed least developed countries, three (the Comoros, the Sudan and Yemen) have policy instruments on wastewater treatment. Notably, Yemen is the only one among them with policies or plans for the safe use of treated wastewater. Only Somalia among these countries has enacted regulations, standards or guidelines addressing faecal sludge treatment.28 Improved access to finance is needed. Policies, strategies and plans do not sufficiently integrate funding considerations. The six least developed countries received only 6.5 per cent of all climate finance for the water sector channelled to the Arab region from 2010 to 2021.29 Capacity-building and other forms of support could help develop bankable projects to facilitate access to finance. More grant finance is needed as many countries are heavily indebted and cannot afford more loans. Capital-intensive projects, such as the development of non-conventional water resources, remain unaffordable for most. For Yemen to address its current water deficit through desalination – which is not the only solution available and may not be sustainable in the long term – it would require 50 large desalination plants with an estimated total operating cost equivalent to 10 per cent of GDP.30 Enhancing local capacities to access additional finance for nature-based local solutions may be financially more viable.

Improved access to finance is needed. Policies, strategies and plans do not sufficiently integrate funding considerations. The six least developed countries received only 6.5 per cent of all climate finance for the water sector channelled to the Arab region from 2010 to 2021.29 Capacity-building and other forms of support could help develop bankable projects to facilitate access to finance. More grant finance is needed as many countries are heavily indebted and cannot afford more loans. Capital-intensive projects, such as the development of non-conventional water resources, remain unaffordable for most. For Yemen to address its current water deficit through desalination – which is not the only solution available and may not be sustainable in the long term – it would require 50 large desalination plants with an estimated total operating cost equivalent to 10 per cent of GDP.30 Enhancing local capacities to access additional finance for nature-based local solutions may be financially more viable.

Djibouti has secured funding for desalination

and wastewater plants from a variety of sources, comprising the State budget, development partners and private investment, including through public-private partnerships. This has allowed the Government to invest heavily in the water sector and increase supplies. For example, the Doraleh desalination plant is operated by a private company under a public-private agreement. In 2021, the Government secured a €79 million loan from the European Investment Bank to finance the expansion of the plant and the construction of three new wastewater desalination plants. One challenge with raising funds for desalination projects is their high energy requirement, which can be expensive. To address this concern, Djibouti is developing renewable energy sources to power its plants.

Djibouti has secured funding for desalination

and wastewater plants from a variety of sources, comprising the State budget, development partners and private investment, including through public-private partnerships. This has allowed the Government to invest heavily in the water sector and increase supplies. For example, the Doraleh desalination plant is operated by a private company under a public-private agreement. In 2021, the Government secured a €79 million loan from the European Investment Bank to finance the expansion of the plant and the construction of three new wastewater desalination plants. One challenge with raising funds for desalination projects is their high energy requirement, which can be expensive. To address this concern, Djibouti is developing renewable energy sources to power its plants.

Source:ESCWA, 2023b.

Source:ESCWA, 2023b.

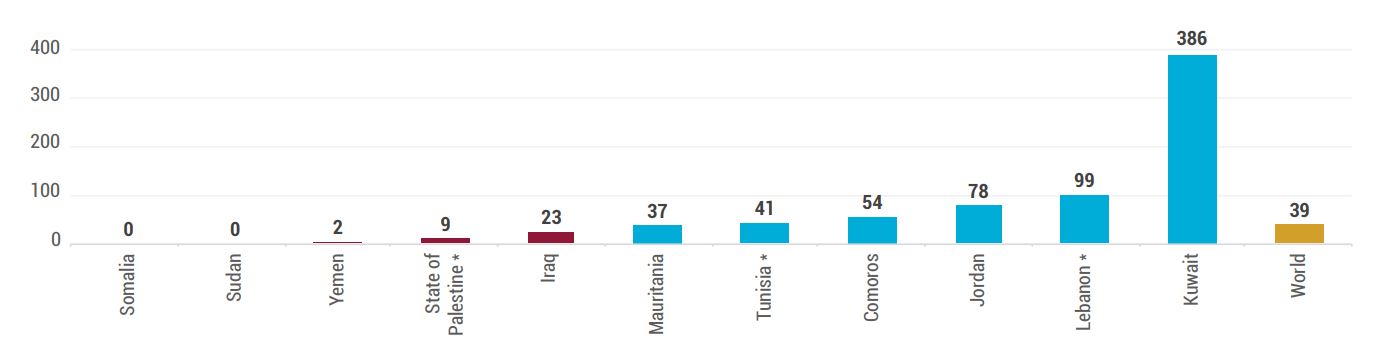

Sources:FAO, 2023; Kuwait, Central Statistical Bureau, 2021.

Sources:FAO, 2023; Kuwait, Central Statistical Bureau, 2021.

Developing local technologies and manufacturing capacities for water desalination and wastewater treatment. Gulf Cooperation Council countries are investing heavily in this area to reduce reliance on imported water and wastewater treatment technologies, and to create jobs and economic opportunities.

Developing local technologies and manufacturing capacities for water desalination and wastewater treatment. Gulf Cooperation Council countries are investing heavily in this area to reduce reliance on imported water and wastewater treatment technologies, and to create jobs and economic opportunities.

In Saudi Arabia, the National Transformation Programme budgeted 300 million Saudi riyals for the localization and transfer of water technology between 2016 and 2021, and 1.2 billion Saudi riyals to localize needed renewable energy technologies to support the local power and water desalination sectors. One initiative is to build a production centre for manufacturing and light industries to fulfil plans for establishing water plants.

In Saudi Arabia, the National Transformation Programme budgeted 300 million Saudi riyals for the localization and transfer of water technology between 2016 and 2021, and 1.2 billion Saudi riyals to localize needed renewable energy technologies to support the local power and water desalination sectors. One initiative is to build a production centre for manufacturing and light industries to fulfil plans for establishing water plants. In the United Arab Emirates, the UAE Water Security Strategy 2036 includes initiatives to promote local technologies and manufacturing capacities for water desalination and wastewater treatment. It calls for establishing a research and development centre for water desalination and wastewater treatment technologies, for example. The Government has already set the strategy in motion by creating the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology, which is dedicated to sustainable technologies, including water desalination and wastewater treatment. The government-run Emirates Water

and Electricity Company has also initiated various programmes to promote local technologies and manufacturing capabilities.

In the United Arab Emirates, the UAE Water Security Strategy 2036 includes initiatives to promote local technologies and manufacturing capacities for water desalination and wastewater treatment. It calls for establishing a research and development centre for water desalination and wastewater treatment technologies, for example. The Government has already set the strategy in motion by creating the Masdar Institute of Science and Technology, which is dedicated to sustainable technologies, including water desalination and wastewater treatment. The government-run Emirates Water

and Electricity Company has also initiated various programmes to promote local technologies and manufacturing capabilities.

Diversifying energy sources for water production, including through the use of renewable energy sources. Gulf Cooperation Council countries are investing in renewable energy and improving the efficiency of water desalination plants to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and improve water security. They are developing new water desalination technologies that are more energy-efficient and cost-effective, which will help to make water desalination more sustainable and affordable.

Diversifying energy sources for water production, including through the use of renewable energy sources. Gulf Cooperation Council countries are investing in renewable energy and improving the efficiency of water desalination plants to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and improve water security. They are developing new water desalination technologies that are more energy-efficient and cost-effective, which will help to make water desalination more sustainable and affordable. Minimizing water supply costs

and increasing

cost recovery without sacrificing service quality.

Gulf Cooperation Council countries are implementing tiered water pricing, reducing water losses from distribution networks, improving public awareness of water conservation measures, and investing in water recycling and reuse technologies.

Minimizing water supply costs

and increasing

cost recovery without sacrificing service quality.

Gulf Cooperation Council countries are implementing tiered water pricing, reducing water losses from distribution networks, improving public awareness of water conservation measures, and investing in water recycling and reuse technologies.

In Saudi Arabia, a revised water tariff structure was introduced in 2015 as a first step towards meeting the goal of full cost recovery stipulated in the Saudi Vision 2030 (see section B for more information). Additionally, the National Transformation Programme has sought to decrease water loss from 25 to 15 per cent by 2020, including by reducing leakage through monitoring the water pipeline system. It also plans to cut the average time to fulfil a water service connection from 68 to 30 business days, and to boost digital content to improve customer service.

In Saudi Arabia, a revised water tariff structure was introduced in 2015 as a first step towards meeting the goal of full cost recovery stipulated in the Saudi Vision 2030 (see section B for more information). Additionally, the National Transformation Programme has sought to decrease water loss from 25 to 15 per cent by 2020, including by reducing leakage through monitoring the water pipeline system. It also plans to cut the average time to fulfil a water service connection from 68 to 30 business days, and to boost digital content to improve customer service. Increasing the economic use of treated wastewater. Gulf Cooperation Council countries have developed a number of regulations to promote the use of treated wastewater for different purposes, including irrigation, industrial use and groundwater recharge. These regulations include setting standards for the quality

of treated wastewater that can be used for different purposes, and developing permitting and inspection procedures. Through public awareness campaigns, school programmes and other initiatives, these countries are educating the public about the safety and reliability of treated wastewater, and the economic and environmental benefits of using it.

Increasing the economic use of treated wastewater. Gulf Cooperation Council countries have developed a number of regulations to promote the use of treated wastewater for different purposes, including irrigation, industrial use and groundwater recharge. These regulations include setting standards for the quality

of treated wastewater that can be used for different purposes, and developing permitting and inspection procedures. Through public awareness campaigns, school programmes and other initiatives, these countries are educating the public about the safety and reliability of treated wastewater, and the economic and environmental benefits of using it.

In Kuwait, Cabinet Resolution No. 12 of 2018 on

the Use of Treated Wastewater in Agricultural and Industrial Sectors mandates that all new agricultural and industrial projects use treated wastewater for at least 50 per cent of their water needs. This regulation has driven greater demand for treated wastewater and encouraged businesses to invest in water recycling and reuse technologies. As a result, there has been a remarkable increase in the use of treated wastewater in recent years. In 2010, only 10 per cent of treated wastewater was put to use; by 2020, this figure had surpassed 50 per cent.

In Kuwait, Cabinet Resolution No. 12 of 2018 on

the Use of Treated Wastewater in Agricultural and Industrial Sectors mandates that all new agricultural and industrial projects use treated wastewater for at least 50 per cent of their water needs. This regulation has driven greater demand for treated wastewater and encouraged businesses to invest in water recycling and reuse technologies. As a result, there has been a remarkable increase in the use of treated wastewater in recent years. In 2010, only 10 per cent of treated wastewater was put to use; by 2020, this figure had surpassed 50 per cent.

Enhancing water-use efficiency and conservation by managing demand and establishing a water-efficient, rational agricultural sector compatible with available water resources. Gulf Cooperation Council countries are implementing water conservation measures in agriculture and industry, reducing water consumption in households, and managing water demand through pricing and regulatory measures to enhance water-use efficiency and conservation.

Enhancing water-use efficiency and conservation by managing demand and establishing a water-efficient, rational agricultural sector compatible with available water resources. Gulf Cooperation Council countries are implementing water conservation measures in agriculture and industry, reducing water consumption in households, and managing water demand through pricing and regulatory measures to enhance water-use efficiency and conservation.

In Saudi Arabia, the National Transformation Programme sought to reduce the municipal water consumption rate per capita from 256 to 200 litres per day by 2020, decrease the volume of renewable water consumption for agricultural purposes from 17 to 10 billion cubic metres, and increase the percentage of agricultural wells with metering gauges installed to 30 per cent.

In Saudi Arabia, the National Transformation Programme sought to reduce the municipal water consumption rate per capita from 256 to 200 litres per day by 2020, decrease the volume of renewable water consumption for agricultural purposes from 17 to 10 billion cubic metres, and increase the percentage of agricultural wells with metering gauges installed to 30 per cent.

The tensions surrounding access to water resources

can be a contributing factor to conflict. Water supplies can also fall victim to conflict, either intentionally or as collateral damage. The politicization and weaponization of water resources remain major challenges. Further, water scarcity and its direct impacts on drinking water availability, sanitation, health and ecosystems can be pull or push factors for migration, often causing additional stresses on areas where water is available.

WASH services often operate below capacity in Arab conflict-affected countries due to degraded and unmaintained infrastructure, frequent power outages and inadequate complementary infrastructure. Conflict and continued unrest have led to the unregulated use of available water resources and the contamination of water sources, heightening the risk of disease outbreaks and waterborne illnesses. Conflict also intensifies displacement, human mobility and the risks associated with daily movements to collect water, including gender-based violence.

Water and sanitation access needs to be secured by repairing and building infrastructure and preparing for risks, including through capacity-building and community participation. Bridging the gap between humanitarian assistance and development aligns with the humanitarian-development-peace nexus approach. Moreover, collaboration between humanitarian and development actors, alongside WASH service providers, is essential for formulating emergency preparedness plans tailored to acute crises.

Water and sanitation access needs to be secured by repairing and building infrastructure and preparing for risks, including through capacity-building and community participation. Bridging the gap between humanitarian assistance and development aligns with the humanitarian-development-peace nexus approach. Moreover, collaboration between humanitarian and development actors, alongside WASH service providers, is essential for formulating emergency preparedness plans tailored to acute crises. There is a need to address water quality concerns and protect human health, such as by managing water sources and treating wastewater to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases. Strategies in Arab conflict-affected countries comprise monitoring and surveillance, water treatment, and public awareness and education.

There is a need to address water quality concerns and protect human health, such as by managing water sources and treating wastewater to prevent the spread of waterborne diseases. Strategies in Arab conflict-affected countries comprise monitoring and surveillance, water treatment, and public awareness and education. Implementing solutions that address the interlinkages and interaction of water and fragility is vital. Conflict-affected countries are shifting towards more integrated approaches, focusing on resilience and sustainability, conflict-sensitive water programming and community-based measures.

Implementing solutions that address the interlinkages and interaction of water and fragility is vital. Conflict-affected countries are shifting towards more integrated approaches, focusing on resilience and sustainability, conflict-sensitive water programming and community-based measures. Existing policies and practices do not sufficiently acknowledge the potential of integrated human mobility solutions in tackling water-related challenges, nor do they recognize IWRM as pivotal in safeguarding the human rights of displaced persons, refugees and migrants.

Existing policies and practices do not sufficiently acknowledge the potential of integrated human mobility solutions in tackling water-related challenges, nor do they recognize IWRM as pivotal in safeguarding the human rights of displaced persons, refugees and migrants. Conflict exacerbates existing gender inequalities in water and sanitation, making women’s inclusion in the sector even more vital. This applies to the adoption of gender-responsive policies as well as the participation of women in decision-making and management. Prioritizing women’s leadership and expertise can address gaps in local capacity created by conflict-induced displacement and casualties. Women’s participation is crucial for building equitable water solutions, especially in conflict zones where women and children bear the burden of water collection.

Conflict exacerbates existing gender inequalities in water and sanitation, making women’s inclusion in the sector even more vital. This applies to the adoption of gender-responsive policies as well as the participation of women in decision-making and management. Prioritizing women’s leadership and expertise can address gaps in local capacity created by conflict-induced displacement and casualties. Women’s participation is crucial for building equitable water solutions, especially in conflict zones where women and children bear the burden of water collection.

Source: ESCWA calculations based on WHO, 2022a.

Source: ESCWA calculations based on WHO, 2022a.

| Inhabitants of rural and remote areas face significant disparities in access to WASH services compared to their urban counterparts. They grapple with much lower levels of access to safe drinking water and sanitation services as well as to basic handwashing facilities within premises. They also have a higher prevalence of open defecation. | In Morocco, the National Strategy for the Development of Rural and Mountainous Areas and the Programme for the Reduction of Territorial and Social Disparities seek to reduce territorial gaps in access to basic services, including drinking water, particularly in rural and mountainous areas. The programme aims to extend the drinking water network over 668 kilometres, install 244 individual connections, dig 9,511 water points and develop 60 drinking water supply networks.a

In Saudi Arabia, the National Transformation Programme allocated 200 million Saudi riyals for water supply social insurance programmes for desert villages between 2016 and 2021. |

|

| Persons living in poverty are more likely to have insufficient water and sanitation facilities and often need to pay more for water than residents in wealthier areas. | In Iraq, the Poverty Alleviation Strategy aims to establish reverse irrigation stations, distribute water sterilization pills and deliver water trucks to groups below the poverty line, while also raising awareness of the importance of using water that meets minimum standards for human consumption.b

In Tunisia, the National Programme for the Sanitation of WorkingClass Neighbourhoods has connected 1,146 low-income neighbourhoods to sanitation networks since 1989, benefiting around 1.4 million people, most from governorates with the greatest needs.c |

|

| Women and girls bear the brunt of inadequate and gender-unresponsive WASH services. These result in heightened maternal morbidity and mortality rates, increased school dropout rates among girls, reduced food security and diminished agricultural livelihoods. Women and girls are also exposed to an elevated risk of sexual abuse and harassment, particularly those who are displaced or live in refugee settlements and places without access to private facilities. | In Somalia, the WASH Sector Strategic Plan (2019–2023) set a national target of 90 per cent of adolescent girls in upper primary and secondary schools having access to menstrual hygiene kits in 2023.d

In the Sudan, the National Water Policy (2016) advocates for gender equality in access to water resources as well as the inclusion of women in decision-making processes and the management of water service providers. Nonetheless, significant gaps remain in implementing the policy and ensuring that women’s needs are met. |

|

| Refugees and IDPs often lack access to safe water and proper sanitation facilities, which increases their vulnerability to illness and disease. | In Jordan, the National Resilience Plan (2014–2016) sought to mitigate the impact of the influx of Syrian refugees on host communities by improving the delivery of WASH services and promoting community participation and awareness-raising among local Jordanian populations and Syrian refugee community groups. The Jordan Response Plan for the Syrian Crisis (2016–2018) dedicated significant resources to expanding wastewater collection and treatment in host communities.e | |

| Migrants often rely on less durable infrastructure, are exposed to frequent disruptions to water and sanitation services, and are among the groups most vulnerable to extreme weather events. Low-skilled migrant workers face discrepancies in access to WASH services due to subpar remuneration, poor work conditions, weak labour inspection systems and a lack of social security. | In Qatar, legislation states that to protect workers from heat stress, employers must provide free and suitably cool drinking water to all workers throughout their working hours.f |

Source: WHO, 2023b.

Source: WHO, 2023b. Source: WHO, 2023b.

Source: WHO, 2023b.

1. Algeria, Bahrain, the Comoros, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen (League of Arab States, 2023).

2. All Arab countries that were Member States of the United Nations with the exception of Mauritania, which was absent.

3. Bahrain, the Comoros, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen (WHO, 2022a; Saudi Arabia, 2018; United Arab Emirates, 2021a).

4. Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen (WHO, 2022a; Algeria, 2014; Qatar, 2018; Saudi Arabian Standards Organization, 2000; United Arab Emirates, 2021a).

5. Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates (WHO, 2022a; United Arab Emirates, 2021a).

6. Bahrain, the Comoros, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Somalia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia and Yemen (WHO, 2022a).

7. Bahrain, the Comoros, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen (WHO, 2022a; WHO, 2018).

8. Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Somalia, the State of Palestine, the Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia (WHO, 2022a).

9. Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the State of Palestine, Tunisia and Yemen (ESCWA, 2016).

10. Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, the State of Palestine, Tunisia and Yemen (ESCWA, 2016).

11. Bahrain, the Comoros, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia and Yemen (WHO, 2022a; Saudi Arabia, 2018).

12. Bahrain, the Comoros, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Somalia, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia and Yemen.

13. Calculations by ESCWA, based on Voluntary National Review reports.

14. Mateo-Sagasta and others, 2023. Figures exclude the Comoros, Djibouti and Somalia.

15. Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, the State of Palestine, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen (WHO, 2022a; Qatar, 2018; United Arab Emirates, 2021b).

16. Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the State of Palestine, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen (WHO, 2022a; Algeria, 2007; Nassif, Tawfik and Abi Saab, 2022; Dare and others, 2017).

17. ESCWA, 2021a.

18. Including Algeria, Bahrain, the Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

19. Including Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the Syrian Arab Republic and the United Arab Emirates.

20. Including Bahrain, Jordan, Lebanon, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the Syrian Arab Republic

21. ESCWA, 2023b.

22. ESCWA and UNEP-DHI Centre on Water and Environment, 2021.

23. ESCWA, 2022a.

24. Bahrain, the Comoros, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, the State of Palestine, the Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia (WHO, 2022a).

25. ESCWA, 2023b. Basic drinking water and sanitation services (SDG indicator 1.4.1) are used here as a proxy for safely managed drinking water and sanitation services (SDG indicators 6.1.1 and 6.2.1) due to insufficient data availability for the least developed countries and other subregions.

26. ESCWA, 2023b.

27. In 2018, a mere 0.6 per cent of population in the Comoros practiced open defecation, with the same rate observed in rural areas.

28. Based on data from WHO (2022a) for five least developed countries (the Comoros, Mauritania, Somalia, the Sudan and Yemen). Information on Djibouti was not available.

29. ESCWA, 2023a.

30. UNDP, 2022.

31. Water policies in Gulf Cooperation Council countries are guided by the Gulf Cooperation Council Unified Water Strategy (2016–2035) and its operational plan.

32. ESCWA, 2022a.

33. ESCWA, 2023a.

34. ESCWA, 2023d.

35. United Nations, 2021a.

36. ESCWA, 2023a.

37. FAO, 2021.

38. ESCWA, 2023b.

39. ESCWA, 2021b.

40. ESCWA, 2023d.

41. UNICEF, 2018.

B’Tselem (2011). The Gap in Water Consumption between Palestinians and Israelis. Accessed on 31 January 2024.

Dare, A. E., and others (2017). Opportunities and Challenges for Treated Wastewater Reuse in the West Bank, Tunisia, and Qatar. Transactions of ASABE, vol. 60, No. 5.

Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP) (2023). Visualisation map of the interlinkages between SDG 6 and the other SDGs. Accessed on 9 June 2023.

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) (2016). Moving towards the SDGs in the Arab Region: Key Findings from the 2016 MDG+ Initiative Report.

__________ (2017). Wastewater: An Arab Perspective.

__________ (2020). Arab Sustainable Development Report 2020.

__________ (2021a). Groundwater in the Arab Region: ESCWA Water Development Report 9.

__________ (2021b). Transboundary Cooperation in Arab States: Second Regional Report on SDG Indicator 6.5.2.

__________ (2022a). Arab Regional Preparatory Meeting for the Midterm Comprehensive Review of the Water Action Decade: Outcome Document.

__________ (2022b). Climate finance needs and flows in the Arab region.

__________ (2023a). Climate finance for water in the Arab region.

__________ (2023b). ESCWA Arab SDG Monitor. Accessed on 22 December 2023.

__________ (2023c). War on Gaza: weaponizing access to water, energy and food.

__________ (2023d). Water sector finance. Committee on Water Resources, fifteenth session Beirut, 19–20 June.

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) and UNEP-DHI Centre on Water and Environment (2021). 2021 Status Report on the Implementation of Integrated Water Resources Management in the Arab Region.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2021). Maghreb Policy Dialogue on the Potential of Non-Conventional Water for Sustainable Agricultural Development in the Arab Maghreb Countries: Ministerial Declaration. 22 March.

__________ (2023). AQUASTAT. Accessed on 7 June 2023.

Infrastructure Transitions Research Consortium (ITRC) and United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) (2018). A Fast Track Analysis of Infrastructure Provision in Palestine.

Kuwait, Central Statistical Bureau (2021). Annual Statistical Bulletin of Environment 2020. Kuwait City.

League of Arab States (2023). Signing and ratifying statement of the updated Arab Charter on Human Rights (Arabic).

Mateo-Sagasta, J., and others (2023). Expanding water reuse in the Middle East and North Africa: Policy Report. Colombo, Sri Lanka: IWMI.

McIlwaine, S. J., and O. K. M. Ouda (2020). Drivers and Challenges to Water Tariff Reform in Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Water Resources Development, vol. 36, No. 6.

Morocco (2023). Développement rural. Accessed on 25 June 2023.

Nassif, Marie Helene, Mohamed Tawfik, and M. T. Abi Saab (2022). Water quality standards and regulations for agricultural water reuse in MENA: from international guidelines to country practices. In Water Reuse in the Middle East and North Africa: A Sourcebook, J. Mateo-Sagasta, M. Al-Hamdi and K. AbuZeid, eds. Colombo, Sri Lanka: IWMI.

Oman (2019). First Voluntary National Review of the Sultanate of Oman 2019.

Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute (MAS) (2013). The new water tariff system in Palestine between economic efficiency and social justice (Arabic).

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2023). An Environmental Catastrophe Threatens Livelihoods in Gaza Strip. Accessed on 31 January 2024.

Qatar (2018). Qatar Second National Development Strategy 2018–2022.

__________ (2020). Decision of the Minister of Administrative Development, Labour and Social Affairs No. 17 for the Year 2021 Specifying Measures to Protect Workers from Heat Stress.

Saudi Arabia (2018). Saudi National Water Strategy 2030 (Arabic).

Saudi Arabian Standards Organization (2000). Un-bottled Drinking Water: SASO 701 and mkg 149 (Arabic).

Somalia (2019). Final Draft: WASH Sector Strategic Plan (2019–2023).

Stockholm International Water Institute (SIWI) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2023). Water Scarcity and Climate Change Enabling Environment Analysis for WASH: Middle East and North Africa.

The Sudan (2018). National Road Map: Sanitation for all in Sudan – Making Sudan Open Defecation Free by 2022.

Tunisia (2021). Rapport national volontaire sur la mise en œuvre des Objectifs de développement durable en Tunisie.

The United Arab Emirates (2021a). Water Quality Regulations 2021.

__________ (2021b). Overview of the National Energy and Water Demand Side Management Programme.

United Nations (2021a). Common Country Analysis (CCA) November 2021: Yemen.

__________ (2021b). Common Country Analysis: Libya.

__________ (2022). Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel: Note by the Secretary-General. A/77/328.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Djibouti (2018). Humanitarian action for children.

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2013). Water Governance in the Arab Region: Managing Scarcity and Securing the Future.

__________ (2022). A Holistic Approach to Addressing Water Resources Challenges in Yemen.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018). A Global Overview of National Regulations and Standards for Drinking Water Quality. Geneva.

__________ (2022a). GLAAS 2021/2022 country survey data. Accessed on 22 December 2023.

__________ (2022b). Strong Systems and Sound Investments: Evidence on and Key Insights into Accelerating Progress on Sanitation, Drinking Water and Hygiene – UN Water Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking Water (GLAAS) 2022 Report. Geneva.

World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) (2023). WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP). Accessed on 22 December 2023.