A significant shift towards sustainable and inclusive industrialization is urgently needed in the Arab region. Infrastructure development is crucial in a context of rising unemployment, the inefficient and unsustainable use of natural resources, increasing debt and protracted crises. Infrastructure projects continue to face serious challenges, including financing constraints, limitations in institutional capacity and crises.

Despite recent strides in R&D, a persistent gap remains between scientific research and the demands of industries and local markets. The volume of research and publications is disconnected from practical technological applications and has little significant impact on economies and societies. There are notable attempts to mainstream technology and seize opportunities from digitalization in various economic sectors, yet the integration of technologies into manufacturing processes is either limited or non-existent. In cases where greater engagement with technologies exists, countries tend to be users instead of developers or exporters. This is especially problematic given the march of the fourth industrial revolution globally, which is leaving the region behind.

SDG 9 is a composite goal that is difficult to fully trace through the policy landscape. This chapter addresses two core policy areas relevant across the Arab region.

The first area encompasses sustainable industrialization policies, with a focus on the manufacturing sector and the development of SMEs. Industrial strategies geared towards economic diversification are means to build sectors that are independent from oil and gas. Policies can focus on accelerating the development of the industrial sector, improving its competitiveness and promoting investments, while encouraging clean production and environmental considerations with clear linkages to SDGs 12 and 13.

The second area entails scientific R&D and innovation, with an emphasis on national strategies and means of implementation, monitoring and funding. Effective R&D strategies translate scientific research into practical applications that respond to the demands of the marketplace. Such strategies are coupled with monitoring frameworks and nationally relevant indicators that go beyond counting the number of researchers or amounts of funding allocated.1

Infrastructure development in the region is mainly undertaken by governments and financed through public funding and multilateral and bilateral lenders. Despite overall progress in developing physical infrastructure in the region, performance across countries and infrastructure types is not uniform. For example, while ICT infrastructure is relatively developed, transport infrastructure is limited in terms of connectivity and logistics, a major challenge to trade and productive sectors such as manufacturing.2 Despite this backdrop, major infrastructure projects with sizeable investments have been launched in several countries, ranging from new cities to transport schemes and nuclear plants.

Infrastructure development in the region is mainly undertaken by governments and financed through public funding and multilateral and bilateral lenders. Despite overall progress in developing physical infrastructure in the region, performance across countries and infrastructure types is not uniform. For example, while ICT infrastructure is relatively developed, transport infrastructure is limited in terms of connectivity and logistics, a major challenge to trade and productive sectors such as manufacturing.2 Despite this backdrop, major infrastructure projects with sizeable investments have been launched in several countries, ranging from new cities to transport schemes and nuclear plants.

The private sector plays a limited but important role through public-private partnerships. Political support to such partnerships is growing with countries taking measures to foster environments that incentivize businesses to provide expertise and help alleviate burdens on public budgets.3 Fifteen Arab countries4 have issued public-private partnership laws or updated existing ones in the past 10 years. The attributes and effectiveness of these laws vary according to national contexts and each country’s legal framework.

Saudi Arabia has launched real estate and infrastructure projects worth $1.25 trillion5 as part of implementing its Vision 2030 and fulfilling an overall objective of economic growth and diversification

as well as increased employment. The Government has invested in the construction of airports, ports, highways and new industrial and tourism zones. Notable megaprojects include NEOM and the Red Sea development project.

Saudi Arabia has launched real estate and infrastructure projects worth $1.25 trillion5 as part of implementing its Vision 2030 and fulfilling an overall objective of economic growth and diversification

as well as increased employment. The Government has invested in the construction of airports, ports, highways and new industrial and tourism zones. Notable megaprojects include NEOM and the Red Sea development project. As part of its Vision 2030, the Government of Egypt has acknowledged that strong infrastructure is a lever for social and economic development. By the end of 2023, infrastructure projects in construction, energy, water and transport were valued at $400 billion.6 The Government is also implementing megaprojects budgeted at more than $10 billion7 for housing, industrial complexes, railways, and undertakings such as the Suez Canal development and the New Administrative Capital.

As part of its Vision 2030, the Government of Egypt has acknowledged that strong infrastructure is a lever for social and economic development. By the end of 2023, infrastructure projects in construction, energy, water and transport were valued at $400 billion.6 The Government is also implementing megaprojects budgeted at more than $10 billion7 for housing, industrial complexes, railways, and undertakings such as the Suez Canal development and the New Administrative Capital. Between 2001 and 2017, Morocco invested between 25 and 38 per cent of its GDP8 in infrastructure development, one of the highest rates globally. Infrastructure projects in transport, water and sanitation, irrigation, ICT and electricity have significantly improved access rates, thus diminishing the gap between rural and urban areas. Factors that have contributed to progress include partnerships with the private sector, strengthened public procurement and facilitation of mixed ownership with state-owned enterprises. Morocco continues to invest mostly in energy, transport and construction, with a current allocation of around $150 billion.9

Between 2001 and 2017, Morocco invested between 25 and 38 per cent of its GDP8 in infrastructure development, one of the highest rates globally. Infrastructure projects in transport, water and sanitation, irrigation, ICT and electricity have significantly improved access rates, thus diminishing the gap between rural and urban areas. Factors that have contributed to progress include partnerships with the private sector, strengthened public procurement and facilitation of mixed ownership with state-owned enterprises. Morocco continues to invest mostly in energy, transport and construction, with a current allocation of around $150 billion.9 Several Arab countries are planning or designing industrial policies to increase the share of manufacturing in GDP and exports as a sector with better prospects for economic diversification and growth (see the chapter

on SDG 8). Industrial policies have been complemented with measures that include identifying niche areas of manufacturing, improving the business environment, strengthening links with scientific research, integrating new technologies, facilitating access to global value chains, promoting exports to global markets and trade negotiations.

Several Arab countries are planning or designing industrial policies to increase the share of manufacturing in GDP and exports as a sector with better prospects for economic diversification and growth (see the chapter

on SDG 8). Industrial policies have been complemented with measures that include identifying niche areas of manufacturing, improving the business environment, strengthening links with scientific research, integrating new technologies, facilitating access to global value chains, promoting exports to global markets and trade negotiations. Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have specified key performance indicators to assess the increased contribution of the industrial sector to GDP.10 Tunisia plans to elevate the contribution of manufacturing to GDP to 20 per cent by 2035.11

Bahrain, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates have specified key performance indicators to assess the increased contribution of the industrial sector to GDP.10 Tunisia plans to elevate the contribution of manufacturing to GDP to 20 per cent by 2035.11 As part of its structural reform, Egypt seeks to boost industrialization through targeted interventions

in manufacturing, agribusiness and ICT. These measures are expected to increase the collective GDP contribution of these sectors to at least 30 per cent by 2024.

As part of its structural reform, Egypt seeks to boost industrialization through targeted interventions

in manufacturing, agribusiness and ICT. These measures are expected to increase the collective GDP contribution of these sectors to at least 30 per cent by 2024. Oman plans to increase the percentage of industrial exports in total exports from 16 per cent in 2015 to 28 per cent in 2040.

Oman plans to increase the percentage of industrial exports in total exports from 16 per cent in 2015 to 28 per cent in 2040. The Saudi Advanced Manufacturing Hub was launched in partnership with the World Economic Forum and aims to make Saudi Arabia a global

hub for industrial innovation and advanced manufacturing. As a result, factories for pharma, aircraft components, metal forming and other industries have been set up, and multinational companies are establishing facilities.

The Saudi Advanced Manufacturing Hub was launched in partnership with the World Economic Forum and aims to make Saudi Arabia a global

hub for industrial innovation and advanced manufacturing. As a result, factories for pharma, aircraft components, metal forming and other industries have been set up, and multinational companies are establishing facilities. The shift in Morocco to targeted industrial policies over two decades has positioned the country as a leader in some industries. For example, reforms to the state-owned phosphate corporate put Morocco in the top five global manufacturers of fertilizers.12

The shift in Morocco to targeted industrial policies over two decades has positioned the country as a leader in some industries. For example, reforms to the state-owned phosphate corporate put Morocco in the top five global manufacturers of fertilizers.12 To support the implementation of industrial policies, middle- and high-income countries are establishing industrial clusters. Established or planned industrial clusters, complexes, parks, poles or cities are evident in at least 13 countries.13 The concentration of resources

(infrastructure, funding and human capacities) in industrial clusters has cultivated a conducive environment for growth and integration into global value chains. Clusters have also brought together different stakeholders, including businesses, government actors and research institutions, although collaboration with academia is still generally weak.

To support the implementation of industrial policies, middle- and high-income countries are establishing industrial clusters. Established or planned industrial clusters, complexes, parks, poles or cities are evident in at least 13 countries.13 The concentration of resources

(infrastructure, funding and human capacities) in industrial clusters has cultivated a conducive environment for growth and integration into global value chains. Clusters have also brought together different stakeholders, including businesses, government actors and research institutions, although collaboration with academia is still generally weak.

Saudi Arabia had established 36 industrial cities by 2021 through its Saudi Authority for Industrial Cities and Technology Zones (Modon), which employs over 570,000 workers and has attracted aggregate private sector investment of over $100 billion.14

Saudi Arabia had established 36 industrial cities by 2021 through its Saudi Authority for Industrial Cities and Technology Zones (Modon), which employs over 570,000 workers and has attracted aggregate private sector investment of over $100 billion.14 Morocco has established 149 industrial zones covering a variety of sectors and helping the automotive sector become the first exporting sector providing over 220,000 job opportunities (see the chapter on SDG 8).15

Morocco has established 149 industrial zones covering a variety of sectors and helping the automotive sector become the first exporting sector providing over 220,000 job opportunities (see the chapter on SDG 8).15 There are some promising efforts to make industries more sustainable. Although industrial policies in the region are generally sector-specific and focused on economic growth, at least eight Arab countries16 have integrated some elements of sustainable industrial development in their policies and considered social and environmental components.

There are some promising efforts to make industries more sustainable. Although industrial policies in the region are generally sector-specific and focused on economic growth, at least eight Arab countries16 have integrated some elements of sustainable industrial development in their policies and considered social and environmental components. The Ministry of Industry and Advanced Technology in the United Arab Emirates seeks to increase the efficiency and sustainability of production cycles and supply chains by driving R&D, setting standards for industrial infrastructure, and implementing policies to reduce resource consumption and support carbon neutrality efforts.

The Ministry of Industry and Advanced Technology in the United Arab Emirates seeks to increase the efficiency and sustainability of production cycles and supply chains by driving R&D, setting standards for industrial infrastructure, and implementing policies to reduce resource consumption and support carbon neutrality efforts. The most recent industrial strategy of Bahrain promotes the circular economy, environmental and social governance, and net-zero carbon emissions.

The most recent industrial strategy of Bahrain promotes the circular economy, environmental and social governance, and net-zero carbon emissions. Morocco plans to enhance the use of green energy and has a policy package including environment laws and financial incentives for reducing industrial pollution.

Morocco plans to enhance the use of green energy and has a policy package including environment laws and financial incentives for reducing industrial pollution. Efforts are underway to strengthen the role of SMEs and improve their competitiveness through focused measures to foster innovation. SMEs in the region account for more than 90 per cent of businesses across different economic sectors, a share that may reach 99 per cent in Algeria.17 To counter barriers to SME growth, national measures are no longer limited to grants or tax exemptions but extend to providing digital transformation services, advice, mentoring, capacity-building, access to funds and links to global value chains. Sixteen Arab countries18 support SMEs through strategies and institutions, or have passed or updated laws to facilitate access to funding, relax restrictions on establishing small firms or simplify business procedures.

Efforts are underway to strengthen the role of SMEs and improve their competitiveness through focused measures to foster innovation. SMEs in the region account for more than 90 per cent of businesses across different economic sectors, a share that may reach 99 per cent in Algeria.17 To counter barriers to SME growth, national measures are no longer limited to grants or tax exemptions but extend to providing digital transformation services, advice, mentoring, capacity-building, access to funds and links to global value chains. Sixteen Arab countries18 support SMEs through strategies and institutions, or have passed or updated laws to facilitate access to funding, relax restrictions on establishing small firms or simplify business procedures. The Tamkeen government agency of Bahrain assists the development of the private sector, offers skills-building services and facilitates access to finance. It focuses on SMEs, start-ups and entrepreneurs, particularly high-potential and innovative ones. In 2022, Tamkeen contributed over $259.95 million to the economy of Bahrain and supported more than 18,400 employment and training opportunities.19

The Tamkeen government agency of Bahrain assists the development of the private sector, offers skills-building services and facilitates access to finance. It focuses on SMEs, start-ups and entrepreneurs, particularly high-potential and innovative ones. In 2022, Tamkeen contributed over $259.95 million to the economy of Bahrain and supported more than 18,400 employment and training opportunities.19 Oman has been shaping and sustaining an enabling environment for SMEs to operate. The Government allows 100 per cent foreign ownership and has set up a one-stop-shop across ports and free trade zones

to reduce red tape and speed the establishment

of enterprises.20 On the financing side, Sharakah is

a closed joint stock company in Oman that offers

a range of services and financial support for SME development. Over 180 SMEs have been assisted

in manufacturing, services and trading. Support

is planned for transformative industries such as hydroponic farms, fish processing, logistics, tourism, technology and innovation.21

Oman has been shaping and sustaining an enabling environment for SMEs to operate. The Government allows 100 per cent foreign ownership and has set up a one-stop-shop across ports and free trade zones

to reduce red tape and speed the establishment

of enterprises.20 On the financing side, Sharakah is

a closed joint stock company in Oman that offers

a range of services and financial support for SME development. Over 180 SMEs have been assisted

in manufacturing, services and trading. Support

is planned for transformative industries such as hydroponic farms, fish processing, logistics, tourism, technology and innovation.21

While gross domestic expenditure on R&D in high-income Arab countries has improved since 2015, it remains less than the global average (figure 9.2), despite important amounts allocated and spent. Gulf Cooperation Council countries are allocating large sums for scientific research, more than $1 billion in Qatar and around $5.12 billion in Saudi Arabia,23 but they may not have sufficient absorptive capacity. While such countries have sophisticated infrastructure and facilities for R&D, expenditure as a share of GDP is small compared to other countries and regions. Another gap, which applies to the region, is that public spending is more focused on research than product development, with limited spending by the private sector.

Industrial strategies integrate industry 4.0 (4IR) technologies. Gulf Cooperation Council countries lead the region on 4IR transformation: four are in the third and fourth quartiles of the best performers on the Global Innovation Index. Most countries in

this group do quite well on the institutions and infrastructure pillars of this index.24 Bahrain, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are focusing their industrial strategies on 4IR technologies as levers to advance industries and boost productivity. Saudi Arabia, for example, is piloting the conversion of industrial plants to modern 4IR technologies25 as part of a wider vision of harnessing technology for economic diversification. A dedicated Saudi Data and AI Authority established in 2019 provides services to integrate AI into all economic sectors.

Industrial strategies integrate industry 4.0 (4IR) technologies. Gulf Cooperation Council countries lead the region on 4IR transformation: four are in the third and fourth quartiles of the best performers on the Global Innovation Index. Most countries in

this group do quite well on the institutions and infrastructure pillars of this index.24 Bahrain, Oman, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are focusing their industrial strategies on 4IR technologies as levers to advance industries and boost productivity. Saudi Arabia, for example, is piloting the conversion of industrial plants to modern 4IR technologies25 as part of a wider vision of harnessing technology for economic diversification. A dedicated Saudi Data and AI Authority established in 2019 provides services to integrate AI into all economic sectors.

The Gulf Cooperation Council countries are conducting free trade negotiations with China, the Republic of Korea and the United Kingdom to strengthen integration into global value chains and expand the export base beyond the traditional oil and gas sectors. These talks seek to open avenues for economic diversification into non-oil industries such as manufacturing, technology, services and other sectors. This shift is expected to lead to the growth of local industries and development of high value-added manufacturing sectors, and encourage the creation of a skilled workforce. Free trade agreements can attract foreign direct investment, fostering innovation, productivity and technological advancements in manufacturing. Although the Gulf Cooperation Council countries work as a bloc, the outcomes will depend on the provisions and conditions of the agreements, including tariff reductions, non-tariff barriers, rules of origin and investment facilitation measures. This policy direction is not exclusive to the Gulf Cooperation Council countries in the region.

The Gulf Cooperation Council countries are conducting free trade negotiations with China, the Republic of Korea and the United Kingdom to strengthen integration into global value chains and expand the export base beyond the traditional oil and gas sectors. These talks seek to open avenues for economic diversification into non-oil industries such as manufacturing, technology, services and other sectors. This shift is expected to lead to the growth of local industries and development of high value-added manufacturing sectors, and encourage the creation of a skilled workforce. Free trade agreements can attract foreign direct investment, fostering innovation, productivity and technological advancements in manufacturing. Although the Gulf Cooperation Council countries work as a bloc, the outcomes will depend on the provisions and conditions of the agreements, including tariff reductions, non-tariff barriers, rules of origin and investment facilitation measures. This policy direction is not exclusive to the Gulf Cooperation Council countries in the region.

R&D priorities in the Gulf Cooperation Council

countries are mainly focused on the technologies of

the future, namely, digital technologies,

such as AI,

robotics and others. These receive higher R&D funding

and are integrated into innovation and other ecosystems

to boost progress. R&D expenditure as a percentage

of GDP remains less than the global average, however,

ranging from 0.1 per cent in Bahrain to 1.5 per cent in

the

United Arab Emirates

. The latter was the only Arab

country allocating more than 1 per cent of its GDP to R&D

in 2021. These countries have also increased the number

of full-time researchers per million inhabitants so that

it is well above the world average.26 Unlike most Arab

countries, where researchers are predominantly employed

in higher education and government, 75 per cent of

research employment in the United Arab Emirates is in the

business sector.27

R&D priorities in the Gulf Cooperation Council

countries are mainly focused on the technologies of

the future, namely, digital technologies,

such as AI,

robotics and others. These receive higher R&D funding

and are integrated into innovation and other ecosystems

to boost progress. R&D expenditure as a percentage

of GDP remains less than the global average, however,

ranging from 0.1 per cent in Bahrain to 1.5 per cent in

the

United Arab Emirates

. The latter was the only Arab

country allocating more than 1 per cent of its GDP to R&D

in 2021. These countries have also increased the number

of full-time researchers per million inhabitants so that

it is well above the world average.26 Unlike most Arab

countries, where researchers are predominantly employed

in higher education and government, 75 per cent of

research employment in the United Arab Emirates is in the

business sector.27

National research and innovation councils are

means for effective governance of R&D and innovation

ecosystems.

Such councils facilitate sectoral coordination

within various scientific disciplines as well as vertical

coordination across levels of government.

Oman, Qatar,

Saudi Arabia

and the United Arab Emirates have each

established a council or authority for research and/

or innovation. Bahrain and Kuwait have considered the

establishment of similar structures.

National research and innovation councils are

means for effective governance of R&D and innovation

ecosystems.

Such councils facilitate sectoral coordination

within various scientific disciplines as well as vertical

coordination across levels of government.

Oman, Qatar,

Saudi Arabia

and the United Arab Emirates have each

established a council or authority for research and/

or innovation. Bahrain and Kuwait have considered the

establishment of similar structures.

The Arab middle-income country group has the highest percentage of manufacturing employment (12.2 per cent) compared to other subregions. The percentage of female researchers in each of Algeria, Egypt, Morocco and Tunisia is higher than the world average (31.2 per cent).28 The percentage of small-scale industries with a loan or line of credit (20.9 per cent) is higher than that of other subregions but the second lowest compared to other regions in the world. National research priorities are selected in a manner that maximizes the benefits of research investments and directs funds towards high-potential areas.

Middle-income countries are using industrial policies to increase job opportunities. To achieve further impact, these policies need to be coupled with a proactive government role in building markets locally and for export, supporting enterprises, facilitating access to finance, building capacity and knowledge, removing infrastructure bottlenecks and encouraging the adoption of technology. Countries have included objectives or targets for increased employment in their industrial policies. For instance, Egypt specified a target of “3 million decent and productive job opportunities” in manufacturing.29 Jordan emphasized increasing opportunities for women in factories and strengthening links between universities and industries to offer training and job opportunities to new graduates. The Faculty for Factory programme of Jordan is one modality to link universities to industry in practical terms.30 The programme has explored areas of collaboration in packaging, chemical industries, food supply and others, and has uncovered challenges in communication between academia and industry and the availability of necessary skills. Morocco reported in 2020 that its industrial acceleration programme led to 405,000 employment opportunities.31 Tunisia aims to increase job opportunities to over 300,000 by 2035 and will improve its position in global value chains positioning through more productive sectors that require skilled labour.

Middle-income countries are using industrial policies to increase job opportunities. To achieve further impact, these policies need to be coupled with a proactive government role in building markets locally and for export, supporting enterprises, facilitating access to finance, building capacity and knowledge, removing infrastructure bottlenecks and encouraging the adoption of technology. Countries have included objectives or targets for increased employment in their industrial policies. For instance, Egypt specified a target of “3 million decent and productive job opportunities” in manufacturing.29 Jordan emphasized increasing opportunities for women in factories and strengthening links between universities and industries to offer training and job opportunities to new graduates. The Faculty for Factory programme of Jordan is one modality to link universities to industry in practical terms.30 The programme has explored areas of collaboration in packaging, chemical industries, food supply and others, and has uncovered challenges in communication between academia and industry and the availability of necessary skills. Morocco reported in 2020 that its industrial acceleration programme led to 405,000 employment opportunities.31 Tunisia aims to increase job opportunities to over 300,000 by 2035 and will improve its position in global value chains positioning through more productive sectors that require skilled labour. Middle-income countries have connected research areas to national priorities that include renewable energy (Algeria, Egypt and Morocco), water (Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia), conservation of natural resources and social sciences. They have also identified niche research areas, such as the pharmaceutical industry in Jordan. Specialized research centres and projects support priority scientific R&D areas. For instance, the Centre for the Development of Renewable Energies in Algeria comes first in terms of the number of patents filed compared with other research centres;32 the country has also launched plans for mega solar energy projects.33 The Research Institute for Solar Energy and New Energies designed the Green Energy Park in Morocco and hosts specialized solar energy laboratories.34 The gap between industry and academia remains, however; industries are focused on production development, market access, risk alleviation and profit-making, whereas academic research is in most cases scientific and not readily convertible into practical applications. Time is also perceived differently; scientific research is usually time intensive whereas in industry, the longer that development or production takes, the more costly it is.

Middle-income countries have connected research areas to national priorities that include renewable energy (Algeria, Egypt and Morocco), water (Egypt, Jordan and Tunisia), conservation of natural resources and social sciences. They have also identified niche research areas, such as the pharmaceutical industry in Jordan. Specialized research centres and projects support priority scientific R&D areas. For instance, the Centre for the Development of Renewable Energies in Algeria comes first in terms of the number of patents filed compared with other research centres;32 the country has also launched plans for mega solar energy projects.33 The Research Institute for Solar Energy and New Energies designed the Green Energy Park in Morocco and hosts specialized solar energy laboratories.34 The gap between industry and academia remains, however; industries are focused on production development, market access, risk alleviation and profit-making, whereas academic research is in most cases scientific and not readily convertible into practical applications. Time is also perceived differently; scientific research is usually time intensive whereas in industry, the longer that development or production takes, the more costly it is.

Extraregional collaboration has boosted scientific research funding and publishing, and introduced new mechanisms for regional cooperation. Bilateral scientific collaborations with countries outside the region have been growing. The United Kingdom and the United States of America are among the top five collaborators for most Arab countries, including middle-income nations. China

is becoming a close collaborator with some countries, such as Egypt. Middle-income countries are also keen to pursue research initiatives with the European Union through initiatives such as EU Horizon 2020.35 These engagements have influenced how funding is allocated, with a shift from block transfers to research institutions to open, transparent competitions assessed through peer review for funding.36

Extraregional collaboration has boosted scientific research funding and publishing, and introduced new mechanisms for regional cooperation. Bilateral scientific collaborations with countries outside the region have been growing. The United Kingdom and the United States of America are among the top five collaborators for most Arab countries, including middle-income nations. China

is becoming a close collaborator with some countries, such as Egypt. Middle-income countries are also keen to pursue research initiatives with the European Union through initiatives such as EU Horizon 2020.35 These engagements have influenced how funding is allocated, with a shift from block transfers to research institutions to open, transparent competitions assessed through peer review for funding.36

Countries are implementing policies and measures to facilitate links between scientific research and industry, towards overcoming barriers to collaboration. Innovation policies in Morocco and Tunisia over the past two decades have focused on establishing innovative, industry-oriented enterprises by linking research institutes and universities to manufacturing. Techno-parks in both countries help implement these policies by connecting universities and enterprises to develop applications that respond to local needs and problems.37 In Egypt, the national science, technology and innovation strategy includes an objective to support investment in scientific research and foster linkages with industry. As a result, law No. 23 of 2018 provides public universities and research institutions that establish start-ups with a legal framework to commercialize their research.38 Jordan has placed considerable emphasis on building an ecosystem for entrepreneurs that leverages innovation. In its national policy on science, technology and innovation, Jordan has included several elements for supporting entrepreneurs and improving coordination between research and trade to facilitate the commercialization of innovative ideas.

Countries are implementing policies and measures to facilitate links between scientific research and industry, towards overcoming barriers to collaboration. Innovation policies in Morocco and Tunisia over the past two decades have focused on establishing innovative, industry-oriented enterprises by linking research institutes and universities to manufacturing. Techno-parks in both countries help implement these policies by connecting universities and enterprises to develop applications that respond to local needs and problems.37 In Egypt, the national science, technology and innovation strategy includes an objective to support investment in scientific research and foster linkages with industry. As a result, law No. 23 of 2018 provides public universities and research institutions that establish start-ups with a legal framework to commercialize their research.38 Jordan has placed considerable emphasis on building an ecosystem for entrepreneurs that leverages innovation. In its national policy on science, technology and innovation, Jordan has included several elements for supporting entrepreneurs and improving coordination between research and trade to facilitate the commercialization of innovative ideas.

The least developed countries are in an embryonic stage of industrial development with limited or no dedicated policies. Infrastructure underdevelopment is among the barriers to the growth of industries, resulting in the limited availability of affordable electricity, inadequate transport systems, and insufficient access to supply and global value chains, among other consequences. Countries that have included industrial development in national policies or development plans focus mostly on the food industry (processing agricultural and fishing products) and small-scale, artisanal industries. The Comoros and Djibouti have included strategic objectives in recent development or SDG acceleration plans to increase the competitiveness of the agrifood, artisanal and construction industries as well as to improve value chains and boost trade. In its newly launched national strategy for manufacturing, Mauritania integrated a focus on the exploitation of its natural resources (agriculture, farming, fishing and renewable energy) for industrial development.

The least developed countries are in an embryonic stage of industrial development with limited or no dedicated policies. Infrastructure underdevelopment is among the barriers to the growth of industries, resulting in the limited availability of affordable electricity, inadequate transport systems, and insufficient access to supply and global value chains, among other consequences. Countries that have included industrial development in national policies or development plans focus mostly on the food industry (processing agricultural and fishing products) and small-scale, artisanal industries. The Comoros and Djibouti have included strategic objectives in recent development or SDG acceleration plans to increase the competitiveness of the agrifood, artisanal and construction industries as well as to improve value chains and boost trade. In its newly launched national strategy for manufacturing, Mauritania integrated a focus on the exploitation of its natural resources (agriculture, farming, fishing and renewable energy) for industrial development.

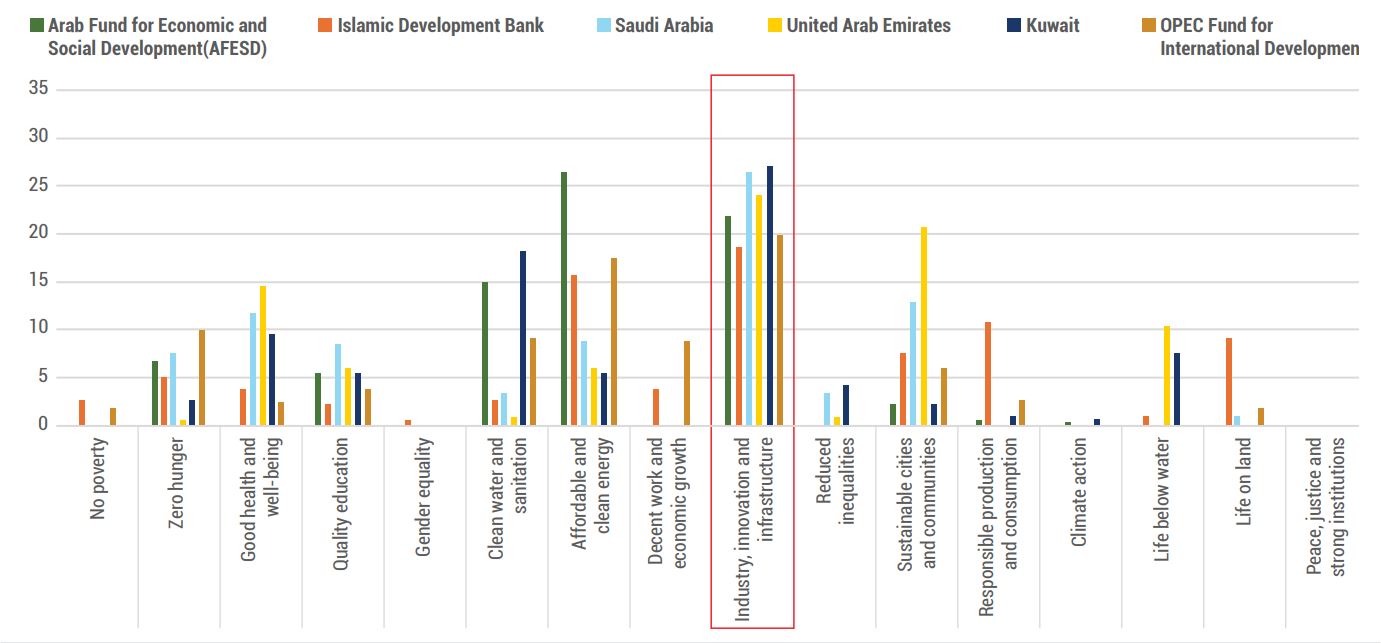

Source: Based on data from ESCWA, 2023b, as of 28 December 2023.

Source: Based on data from ESCWA, 2023b, as of 28 December 2023.

The evolving policy landscape in the least developed countries shows rising awareness of the importance of science, technology and innovation, and the governance of its systems. For instance, Mauritania has developed a strategy for scientific research and established

a supreme council for research, and is working on building a governance system for R&D and an innovation ecosystem.

The evolving policy landscape in the least developed countries shows rising awareness of the importance of science, technology and innovation, and the governance of its systems. For instance, Mauritania has developed a strategy for scientific research and established

a supreme council for research, and is working on building a governance system for R&D and an innovation ecosystem. Conflict has resulted in the breakdown of R&D systems, physical destruction of infrastructure and stalled manufacturing. It poses a major barrier to regional integration, affecting supply chains and impeding the movement of goods. The Sudan in 2017 issued a science, technology and innovation policy and had plans to increase spending on R&D. The resurgence of conflict

in 2023, however, halted implementation and severely disrupted the functioning of educational institutions.

Conflict has resulted in the breakdown of R&D systems, physical destruction of infrastructure and stalled manufacturing. It poses a major barrier to regional integration, affecting supply chains and impeding the movement of goods. The Sudan in 2017 issued a science, technology and innovation policy and had plans to increase spending on R&D. The resurgence of conflict

in 2023, however, halted implementation and severely disrupted the functioning of educational institutions.

Considerable opportunities lie ahead for countries emerging from conflict, with a focus on infrastructure. The rebuilding phase carries prospects for industrial development that can be connected from the onset to green and inclusive industrialization as well as technology. This will require collective efforts by governments, non-state actors and the donor community to ensure that local talents and skills become part of the rebuilding process. The Syrian Arab Republic has already identified research priorities and conducted needs assessments during 2018–2020. Plans are underway for legal reforms, research units, and connections between researchers and investors.41

Considerable opportunities lie ahead for countries emerging from conflict, with a focus on infrastructure. The rebuilding phase carries prospects for industrial development that can be connected from the onset to green and inclusive industrialization as well as technology. This will require collective efforts by governments, non-state actors and the donor community to ensure that local talents and skills become part of the rebuilding process. The Syrian Arab Republic has already identified research priorities and conducted needs assessments during 2018–2020. Plans are underway for legal reforms, research units, and connections between researchers and investors.41

| Arab least developed and conflict-affected countries that do not have science, technology and innovation policies or capacities to implement them are at risk of being left behind. Armed conflict creates additional obstacles by destroying infrastructure and factories. | The United Nations Technology Bank for Least Developed Countries is conducting research on science, technology and innovation needs. It also aims to facilitate technology and knowledge transfer as well as resource mobilization. A technology needs assessment is currently underway in Djibouti. The bank also offers capacitybuilding programmes to researchers, students and entrepreneurs. A programme for strengthening and establishing national science academies has already led to the formation of new academies in least developed countries outside the Arab region; the bank has committed to providing similar support in North Africa.

a

Mauritania recently launched innovation incubators that support and fund young entrepreneurs aiming to build innovative businesses. The most notable are the Kosmos Innovation Center and the Hadina RIMTIC. They operate within a wider national effort to improve the R&D and innovation ecosystem, including by establishing a national council and an innovation unit, and developing an R&D strategy. b |

|

| Women: Despite the rising number of female graduates in science and technology fields, women remain underrepresented in employment in these sectors. Further, the expected increase in automation and the integration of 4IR technologies will affect low-skilled and repetitive manual labour jobs where women often concentrate. | In Oman, Bank Muscat offers services to support and encourage women entrepreneurs at different stages of business growth. It also collaborates with Riyada – the Public Authority for SME Development to provide leadership development opportunities and vital connections to help advance women’s businesses.

c

In Egypt, the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Agency collaborated with the United Nations Development Programme to offer loans that have reached more than 520,000 of these businesses; 48 per cent of beneficiaries have been women. d |

|

| Older employees/workers: Increased overlap between technology and industries has accompanied a perception that older employees/workers may be unwilling to embrace new technologies such as Artificial Intelligence. The speed at which digital technology is advancing will require the upskilling and reskilling of employees, an issue not yet widely addressed in the region. This is particularly important for employees over 55 years of age. | In Saudi Arabia, 47 per cent of employers are training staff to cover gaps in expertise. The Digital Government Authority launched a programme to develop digital skills in the public sector in partnership with local and global academic institutions. e |

National development banks can support economic agents to ensure the continuity of their operations in times of economic turbulence. This will require developing human resources and building skills.47 The Qatar Development Bank has been investing in the SME ecosystem and has launched initiatives such as the Export Development and Promotion Agency, TASDEER, and the Qatar Business Incubation Centre; both support local production. The bank also has an SME equity fund and recognizes excellence through special awards.48 The Oman Development Bank offers facilities to SMEs and microenterprises in a number of industrial sectors, including manufacturing, technology and logistics. In 2021, it approved OMR 54 million ($140.3 million) for loans, with the highest allocation going to enterprises in the manufacturing sector.49

National development banks can support economic agents to ensure the continuity of their operations in times of economic turbulence. This will require developing human resources and building skills.47 The Qatar Development Bank has been investing in the SME ecosystem and has launched initiatives such as the Export Development and Promotion Agency, TASDEER, and the Qatar Business Incubation Centre; both support local production. The bank also has an SME equity fund and recognizes excellence through special awards.48 The Oman Development Bank offers facilities to SMEs and microenterprises in a number of industrial sectors, including manufacturing, technology and logistics. In 2021, it approved OMR 54 million ($140.3 million) for loans, with the highest allocation going to enterprises in the manufacturing sector.49

Specialized national funds: The Saudi Industrial Development Fund supports competitive enterprises with a view to diversifying the economy of Saudi Arabia. Its mandate has been aligned with Saudi Vision 2030. In the past decade, the fund has approved 1,545 medium- and long-term loans for industrial projects amounting to SAR 107 billion ($28.5 billion). The fund saw capital growth from SAR 40 billion in 2012 to SAR 105 billion in 2019.50

Specialized national funds: The Saudi Industrial Development Fund supports competitive enterprises with a view to diversifying the economy of Saudi Arabia. Its mandate has been aligned with Saudi Vision 2030. In the past decade, the fund has approved 1,545 medium- and long-term loans for industrial projects amounting to SAR 107 billion ($28.5 billion). The fund saw capital growth from SAR 40 billion in 2012 to SAR 105 billion in 2019.50 Regional development banks: These banks secure and mobilize resources to support governments of developing countries with infrastructure and economic projects. They also focus on regional integration by backing joint country projects. The Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development has committed over $36 billion in loans since its establishment. From 2019 to 2021, loans for infrastructure and productive sectors topped $1.7 billion.51 Over the same period, loans from the Islamic Development Bank to Arab countries for infrastructure and productive sectors exceeded $310 million, with most going to Lebanon and Mauritania.52

Regional development banks: These banks secure and mobilize resources to support governments of developing countries with infrastructure and economic projects. They also focus on regional integration by backing joint country projects. The Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development has committed over $36 billion in loans since its establishment. From 2019 to 2021, loans for infrastructure and productive sectors topped $1.7 billion.51 Over the same period, loans from the Islamic Development Bank to Arab countries for infrastructure and productive sectors exceeded $310 million, with most going to Lebanon and Mauritania.52 Attracting foreign direct investment: In Morocco, foreign direct investment for industrial development

is becoming more important. Morocco has attracted substantial flows by taking concrete actions that drew investors – namely, infrastructure upgrades, upskilling and ecosystem building – instead of pursuing subsidies or tax exemptions (see the chapter on SDG 8).53

Attracting foreign direct investment: In Morocco, foreign direct investment for industrial development

is becoming more important. Morocco has attracted substantial flows by taking concrete actions that drew investors – namely, infrastructure upgrades, upskilling and ecosystem building – instead of pursuing subsidies or tax exemptions (see the chapter on SDG 8).53 Financing sustainable industrial transformation: This requires scaled-up, coordinated, and targeted public and private investments. On the public sector side, measures are needed to incentivize private investments using fiscal and financial instruments. Examples include enacting tax credits or spurring demand through public procurement that is innovative or green. Public development banks can assume a role in filling resource and knowledge gaps (market intelligence) and regulatory measures can incentivize commercial lending through risk-sharing. The proportion of small-scale industries with a loan or line of credit (15.2 per cent) is still around half the global value and less than any other region worldwide (figure 9.6).

Financing sustainable industrial transformation: This requires scaled-up, coordinated, and targeted public and private investments. On the public sector side, measures are needed to incentivize private investments using fiscal and financial instruments. Examples include enacting tax credits or spurring demand through public procurement that is innovative or green. Public development banks can assume a role in filling resource and knowledge gaps (market intelligence) and regulatory measures can incentivize commercial lending through risk-sharing. The proportion of small-scale industries with a loan or line of credit (15.2 per cent) is still around half the global value and less than any other region worldwide (figure 9.6). Source: Based on data from ESCWA, 2023b, as of December 2023.

Source: Based on data from ESCWA, 2023b, as of December 2023.

1. The relationship between the number of researchers and amounts of R&D funding versus innovation output is not necessarily linear.

2. OECD, 2021.

3. Ibid.

4. The Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, the State of Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates.

5. Zawya, 2023.

6. MEED, 2023a.

7. Egypt, 2021.

8. World Bank, 2020b.

9. MEED, 2023b.

10. See for example: Qatar Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2018; United Arab Emirates, 2023.

11. Tunisia Ministry of Industry, Energy and Mines, 2022.

12. Tanchum, 2022.

13. Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the State of Palestine, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates.

14. Saudi Authority for Industrial Cities and Technology Zones – Modon, 2021.

15. Morocco Ministry of Industry and Trade, 2023; Zawya, 2021; Riera and Paetzold, 2020.

16. Bahrain, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates.

17. European Union, 2023.

18. Algeria, Egypt, Kuwait, Mauritania, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and the United Arab Emirates have laws and Bahrain, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, the State of Palestine and the Syrian Arab Republic have structures, strategies or initiatives to offer support or finance. For more information, visit ESCWA’s Arab SMEs Portal.

19. Tamkeen, 2023.

20. Zawya, 2020; Sohar, 2023.

21. Sharakah, 2023.

22. World Bank, 2023.

23. Invest Qatar, 2023; Saudi Arabia’s General Authority for Statistics, 2022.

24. WIPO, 2022.

25. Arab News, 2021.

26. In 2020, the number of researchers (full-time equivalent) per million inhabitants in the United Arab Emirates was 2,489 compared to a global average of 1,353. ESCWA, 2023b, accessed December 2023.

27. UNESCO, 2021.

28. UNESCO, 2022.

29. Egypt Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2015.

30. Al Abdallat and Tutunji, 2012.

31. Morocco, 2020.

32. UNESCO, 2021.

33. Attaqa, 2022.

34. UNESCO, 2021.

35. European Commission, 2022.

36. Arvantis and Hanafi, 2019.

37. Dossou and Hanaa, 2020.

38. El-Sayed and Ghoneima, 2022.

39. The State of Palestine, Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Technology, 2019.

40. World Bank, 2018.

41. UNESCO, 2021.

42. Noumba Um, 2020.

43. The National Fund for Small and Medium Enterprise Development, 2023.

44. UNESCO defines five main sources for R&D funding as: business enterprise, government, higher education, private non-profit and the rest of the world.

the world.45. UNESCO, 2021.

46. ITU, 2020.

47. UNIDO, 2021a.

48. Qatar Development Bank, n.d.

49. Oman Development Bank, 2021.

50. Saudi Industrial Development Fund, 2021.

51. Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development, 2022.

52. Islamic Development Bank, 2022.

53. Cherkaoui, 2023.

54. Hussein, 2023; Bahrain Ministry of Industry and Commerce, n.d.

55. The Peninsula, 2022.

56. UNIDO, 2023.

57. UNESCO, 2021.

Al Abdallat, Y., and Tutunji, T. (2012). Faculty for Factory program: A University-industry link in Jordan.

Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development (AFESD) (2022). AFESD’s annual reports.

Arab News (2021). Saudi Arabia prepares 100 plants for the fourth industrial revolution.

Alarabiya (2021). Saudi Arabia – digital government authority launches capacity building programme Quodrat Tech.

Arvantis, R., and S. Hanafi (2019). Research policy in Arab countries: international cooperation, Competitive Calls, and Career Incentives. In The Transformation of Research in the South: Policies and Outcomes. Marseille: IRD Éditions.

Attaqa (2022). Renewable energy by 2030. Algeria competes with Morocco for leadership in the region (Arabic).

Bahrain, Ministry of Industry and Commerce (n.d.). Industrial partnership.

Bank Muscat (2023). Al Wathbah.

Cherkaoui, M. (2023). Industrial and regional policies in MENA: survey of economists. Economic Research Forum.

Dossou, L., and Hanaa, I. (2020). Development of innovation policy: Case study of north and West African countries. SHS Web of Conferences 89.

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) (2017). National Technology Development and Transfer System in Mauritania. Beirut. __________ (2023a). Background note on SDG 9.

__________ (2023b). ESCWA Arab SDG Monitor.

__________ (2023c). Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals in the Arab Region. Beirut.

__________ (2024). Annual SDG Review 2024: Skills development, innovation and the private sector in the Arab region. Beirut.

Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) and University of St Andrews (2020). Syria at War – Eight Years On.

Egypt (2021). Voluntary National Review 2021.

Egypt, Ministry of Trade and Industry (2015). Industry and Trade Development Strategy 2016–2020.

European Commission (2021). Updates on the Association of Third Countries to Horizon Europe.

__________ (2022). EU-Mediterranean Cooperation in Research and Innovation. Publications Office of the European Union.

__________ (2023). Research and innovation – Mediterranean.

European Union (2023). MED MSMEs policies for inclusive growth – Algeria.

Hussein, H. (2023). UAE, Egypt, Jordan and Bahrain Sign $2bln of industrial agreements. Zawya, 27 February.

The Institute of Engineering and Technology (2022). Engineering and technology skills in the United Arab Emirates.

__________ (2023). Engineering and technology skills in the Sultanate of Oman.

International Telecommunication Union (ITU) (2020). Assessing Investment Needs of Connecting Humanity to the Internet by 2030. Invest Qatar (2023). Sectors and opportunities: education.

Islamic Development Bank (2022). Annual reports.

Kleiner-Schaefer, T., & Schaefer, K. (2022). Barriers to university–industry collaboration in an emerging market: Firm-level evidence from Turkey. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 47, 872–905.

Mantlana, K. B., and M. A. Maoela (2019). Mapping the Interlinkages between sustainable development goal 9 and other sustainable development goals: a preliminary exploration. Business Strategy and Development, 13 December.

Al Maskry, F. (2016). Riyada, Bank Muscat join hands to support women entrepreneurs initiatives. Oman Daily Observer.

Middle East business intelligence (MEED) (2023a). Egypt 2024 country profile and databank.

__________ (2023b). Morocco 2024 country profile and databank.

Morocco (2020). Voluntary National Review 2020.

Morocco, Ministry of Industry and Trade (2023). Key figures.

The National Fund for Small and Medium Enterprise Development (2023). Main website.

Noumba Um, P. (2020). Building forward better in MENA: How infrastructure investments can create jobs. World Bank Blogs.

Oman Development Bank (2021). Annual Report 2021.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2017). How Arab countries and institutions finance development.

__________ (2021). Middle East and North Africa Investment Policy Perspectives. Paris.

The State of Palestine, Ministry of Telecommunications and Information Technology (2019). Policy Agenda to Support Palestine ICT Startup Ecosystem. The Peninsula (2022). “Karwa” to operate massive bus fleet to serve World Cup fans.

PwC (2022). The Hopes and fears of employees across the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Qatar Development Bank (n.d.). Role of QDB in supporting entrepreneurship and SMEs in Qatar.

Qatar, Ministry of Commerce and Industry (2018). Qatar National Manufacturing Strategy 2018–2022.

Riera, O., and P. Paetzold (2020). Global value chains diagnostic – case study: automobiles made in Morocco. European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Saudi Authority for Industrial Cities and Technology Zones – Modon (2021). Annual Report 2021. Saudi Industrial Development Fund (2021). Annual Report 2021.

El-Sayed, K., and M. Ghoneima (2022). Science, Technology, Innovation and Digitalization. In M. Mohieldin, ed., Financing Sustainable Development In Egypt Report. Cairo: League of Arab States.

Sharakah (2023). Ruwad Sharakah.

Sohar (2023). Sohar One Stop Shop.

Tamkeen (2023). Tamkeen Annual Plan 2023.

Tanchum, M. (2022). Morocco’s new challenges as a gatekeeper of the world’s food supply: the geopolitics, economics, and sustainability of OCP’s global fertilizer exports. Middle East Institute.

Tunisia, Ministry of Industry, Energy and Mines (2022). Tunisia Industrial and Innovation Strategy 2035.

United Nations (2023a). Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2023: Financing Sustainable Transformations. New York: Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development.

United Nations (2023b). Technology Bank for the Least Developed Countries.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2021). UNESCO Science Report: the race against time for smarter development. Paris.

__________ (2022). UNESCO Institute for Statistics Database. Accessed on 1 July 2023.

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) (2021a). Industrial Development Report 2022. The Future of Industrialization in a Post-Pandemic World. Vienna.

__________ (2021b). Statistical Indicators of Inclusive and Sustainable Industrialization – Biennial Progress Report 2021.

__________ (2023). An overview of the industrial deep decarbonisation initiative.

__________ (2024). Independent Terminal Evaluation – Job Creation for Youth and Women through Improvement of Business Environment and SMEs Competitiveness. United Nations Technology Bank for the Least Developed Countries (2022).

World Bank (2018). Tech Startup Ecosystem in West Bank and Gaza.

__________ (2020a). Updated dynamic needs assessment for Yemen.

__________ (2020b). Morocco Infrastructure Review.

World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) (2022). Global Innovation Index 2022: What Is the Future of Innovation-Driven Growth. Geneva.

Yalçıntaş, M., Çiflikli Kaya, C., & Kaya, B. (2015). University-Industry Cooperation interfaces in Turkey from academicians’ perspective. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 62–71.

Zawya (2020). 100% foreign ownership now possible in most Omani businesses.

__________ (2021). Morocco becomes Africa’s new automotive manufacturing hub.

__________ (2023). Saudi megaprojects: value of construction deals reaches $250bln.